Some of the rulers of the Languedoc and their relatives are buried in the Cistercian Abbey at Fontevrault, a "double" house with both monks and nuns. Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse was interred in there, along with his grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, his mother Jeanne of England and his plantagenet uncle, King Richard I of England.

Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the Languedoc

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Cathars, Catholics and Waldensians

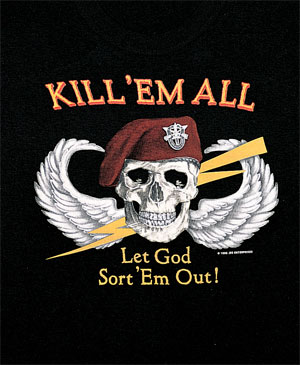

This page covers the role of representatives of the Roman Catholic Church, notably the Cistercian Order, the Dominican Order, and the Franciscan Order. We then look at the The Cathar View of the Roman Catholic Church and the The Roman Catholic View of the Cathar Church, dealing in detail with Catholic Propaganda and specificall with propaganda concerning Blasphemy, Marriage, Incest, Homosexuality, Bestiality, Contraception, Sexual Equality, Other Sex Crimes, Vegetarianism, The Natural Order, and Suicide. This section also covers the question of whether the words "Kill Them All, God will know his own" were ever spoken by a crusade leader; and also the relationship between the The Cathar Church and the Waldensian Church Cathars and local Catholics in the Languedoc seem to have lived happily together for over a century. We have no record of a single incident of friction between the two faiths before the early thirteenth century - indeed we know that Cathars and Catholics coexisted not just within the territories of the Counts of Toulouse and Foix, and of the Viscount of Beziers and Carcassonne, but within each fief, each town and even within many families. It was surprisingly common for even Catholic priests to have become Cathar believers. The papacy became increasingly allarmed as the power of the Catholic Church diminished along with tithes and a range of other Church taxes. The Church successively tried small punitive military expeditions (as at Lavaur), a preaching campaign and a series of public debates between Cathars and Catholics. The military expeditions of the twelvth century were successful but too small scale to have a significant impact. The preaching campaignes and public debates on the other hand were utter failures. All of these initiatives had been driven by the Cistercians, though the followers of Dominic Guzmán (an Augustinian Cannon) had also engaged, in preaching and public debating, but withan equal lack of success. As the failures mounted, popes had tried on a number of occasions to mobilise full scale crusades against the Cathars, but without success. in 1207 the murder of a Cistercian papal legate provided a new more concrete justification for a crusade. Previous attempts had failed largely because the King of France was fully engaged fighting the Plantagenate Kings of England. By 1207 the pressure had been reduced (King John having lost most of his continental lands). The King of France allowed some of his senior vassals to answer the call for a crusade. The head of the Cistercian Order, Arnaud Amaury, the Abbot of Citeau, another papal legate, was appointed to lead the Crusade, handing over military command only after the massacre of Beziers and the surrender of Carcassonne. The Crusade succeded militarily, killing an unknown number of Cathars and Catholics alike. But Catharism still enjoyed extensive support among the broad population of the Languedoc. To extirpate the faith entirely a new approach was needed. Dominic Guzmán's followers had formed a new order, formally recognised in 1216. Properly called the Preacher-Brothers they are more commonly called the Dominicans. This new Dominican order acting on the authority of papal legates formed the kernal of new papal Inquisition, an approach formally approved later by the Papacy - so that Dominican Inquisitors were answerable directly to the pope (rather like a new set of papal legates). The Dominican Inquisitors proved highly effective, but were widely hated. In response to widespead complaints by Lords and nascent city councils alike, Dominican Inquisitors were supplemented by representitives of the Franciscan Order (presumably to soften to approach). In practice the Franciscans were not always sympathetic to the Dominican approach, and at least one was himself charged after he had lead popular opposition to Dominican excesses and alleged corruption. For Cathars the Catholic Church represented a strand of Christianity that had gone badly astray in the fourth century. Cathars saw themselves as true Christians, retaining the Christian beliefs and practices of the Early Christian Church. In this they were of course a mirror image of the Catholic Church. It too saw itself as representing the One True Church, and saw any deviation from its teachings as heresy. In other words both sides saw themselves as True Christians, and the other side as deviants who had lost their way. Both sides saw the other as intrinically evil, and subject to the rule of of a satanic being. Specifically, Cathars saw the Catholic Church as the Whore of Babylon, referred to the Book of Revelation. Click here for more on the Cathar View of the Roman Catholic Church. The Catholic Church never quite decided whether Catharism was a Christian heresy or a religion quite separate from Christianity. For a long time it held Catharism to be a revival of Manichaeism for the early Christian period, but this position seems to have been abandoned. Click here for more on he Roman Catholic View of the Cathar Church To counter Catharism the Roman Catholic Church developed an extensive battery of propaganda concerning Cathar beliefs and practises, including blasphemy, marriage, incest, homosexuality, bestiality, contraception, sexual equality, other sex crimes, vegetarianism, the natural order, and suicide.

Kill Them All ....

In recent times some people have started to voice doubts about whether Arnaud Amaury ever spoke the words attributed to him "Kill Them All ...". This has become a point of contention between Catholic apologists and others. For a summary of the relevant arguments on both sites along with sources, click on this link.

The Cathar Church and the Waldensian Church

A group of dissident Catholics who came to be known as Waldensians or Vaudois flourished during the same period as the Cathars. Although the two groups shared almost nothing in common, the Waldensians came to be regarded as heretics, and Catholic Sources often fail to distinguish Cathars from Waldensians, either confusing them or assuming that their heresies were identical. Click on the following link for more on the Cathar Church and the Waldensian Church

Summary of this Page

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cistercians, Cistercian Abbeys

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Church

|

8. Dormitory

|

|

|

Relaxations were introduced with respect to rules around diet and simplicity of life, and also in regard to the sources of income. Rents and tolls were admitted and benefices incorporated, as was already standard among the Benedictines. Farming operations tended to promote a commercial ethos, and the Order became fabulously wealthy. Splendour and luxury became a feature of many Cistercian monasteries, and the choir monks abandoned even the pretence of working in the fields. Then their influence began to wane, largely because of their unwieldy size, their extensive corruption, and the rise of the mendicant orders - the Dominicans and the Franciscans.

The later history of the Cistercians is largely one of unsuccessful attempted revivals and reforms. In the 17th century an effort at a general reform was made, promoted by the pope and the king of France. The General Chapter elected Richelieu as commendatory abbot of Cîteaux, thinking that he would protect them from the threatened reform. In fact Richelieu tried his best to promote reform, but the endemic corruption was too deep, and he proved another in a long line of failed reformers. A later attempt at reform resulted in the formation (1663) of the Trappists.

|

Commendatory Abbots. A commendatory abbot is someone who holds an abbey in commendam, that is, who drawsits revenues and may have some jurisdiction, but in theory does not exercise any authority over its inner monastic discipline. Originally only vacant abbeys were given in commendam. As early as the time of Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) vacant abbeys were given in commendam to bishops who had lost their episcopal sees. The practice began to be abused in the eighth century. Often commendatory abbots were laymen authorised to draw the revenues and manage the temporal affairs of the monasteries in reward for military services. As the Catholic Encyclopedia admits "The most worthless persons were often made commendatory abbots, who in many cases brought about the temporal and spiritual ruin of the monasteries". Abuses in France at least were stopped at French Revolution and the secularization of monasteries in the beginning of the eighteenth century. Since that time commendatory abbots have become rarer, though they still exist. There are still commendatory abbots among the cardinals in Rome. |

The Reformation and the later revolutions of the 18th century almost wholly destroyed the Cistercians. A few survived and there are still working Cistercian monasteries today. There are about 100 Cistercian monasteries around the world and about 4700 monks, including lay brothers.

Cistercian Abbeys in the Languedoc-Roussillon include:

- Fontfroide Abbey. One of the great Cistercian

abbeys (XIIth century) in an excellent state of preservation.

Privately owned, but open to the public. It is in the Aude

département. Olivier de Termes

is though to be buried here in the chapel of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

Click on the following link for more on the Fontfroide Abbey

- Lagrasse Abbey. in the

Corbières in the Aude

département. Click on the following link for more on

the Abbey of Lagrasse

Lagrasse Abbey

- Saint-Papoul. in the Aude

département. Click on the following link for more on

the

Saint-Papoul Abbey

- Saint-Hilaire. In the Aude

département. Click on the following link for more on

the

Saint-Hilaire Abbey

- Alet les Bains in the Aude

département. Click on the following link for more on

the Abbey

at Alet-les-Bains

- Villelongue in the Aude département

- Saint Polycarpe in the Aude département

- Caunes-Minervois in the Aude département

- Saint Martin Le Vieil in the Aude département

- Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert in the Hérault

département. Click on the following link for more on

the

Abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Desert

- Abbaye de Valmagne www.valmagne.com This

is a well preserved Medieval Cistercian abbey in the Hérault

département, now in private hands. The abbey church

dates from 1257, shortly after the end of the Crusade against

the Cathars. The owners have won many prizes for the work done

to restore the Abbey. It is classified as an Historical Monument

and is open to visitors every day in summer and the afternoon

in winter. Medieval gardens. Vinyards. Events. You can stay at

the associated Auberge de frère Nonenque. The abbey

is also available for receptions. Click on the following link

for more on the Abbaye

de Valmagne

- Chartreuse de Valbonne: in the Gard Département Large medieval monastery located in a forest.

- Saint-Félix-de-Montceau in the Hérault département,

- Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa in the Pyrénées-Orientales Département. Benedictine monks have been here since 578. The Abbey is pre-Romanesque and the cloister (in pink marble) Romanesque.

- Saint-Martin-du-Canigou in the Pyrénées-Orientales Département. Abbey Church and cloister of the XI-XIIth centuries.

- Prieuré de Serrabona (literally, the Priory of the Good Mountain) in the Pyrénées-Orientales.

|

||

Dominicans

The Order of Preachers (Latin: Ordo Praedicatorum, hence the abbreviation OP used by members), is more commonly known since the 15th century as the Dominican Order or Dominicans. It is a Roman Catholic religious order founded in the Languedoc by the Spanish canon Dominic Guzmán, and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216.

After Dominic completed his studies, Bishop Martin Bazan and Prior Diego d'Achebes appointed him to the cathedral chapter and he became a regular canon under the Rule of St Augustine and the Constitutions for the cathedral church of Osma. At the age of twenty-four or twenty-five, he was ordained to the priesthood.

Membership in the Order includes friars, nuns, active sisters, and lay or secular Dominicans affiliated with the Order. The friars are all ordained Catholic priests. Members of the order generally carry the letters O.P., standing for Ordinis Praedicatorum, meaning of the Order of Preachers, after their names.

It was founded to combat Catharism, and Domnicans soon established the Inquisition when it became apparent that preaching and debating produced almost no converts from Catharism. (The first Grand Inquistor of Spain, Tomás de Torquemada, was also a Dominican). Their identification as Dominicans gave rise to the pun that they were the Domini canes, or Hounds of the Lord.

In England and other countries the Dominican friars are referred to as Black Friars because of the black cappa or cloak they wear over their white habits between Halloween and Easter. Dominicans were Blackfriars, as opposed to Whitefriars (such as Carmelites) or Greyfriars (Franciscans). They are also distinct from the Augustinian Friars (the Austin friars) who wear a similar habit. (Dominic Guzmán had been an Augustinian canon).

In France, the Dominicans were known as Jacobins, because their convent in Paris was attached to the church of Saint-Jacques, now disappeared, on the way to Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas, which belonged to the Italian Order of San Giacomo dell Altopascio - St. James in English - Sanctus Jacobus in Latin.

The Dominican Order came into being in the Middle Ages at a time when men of God were no longer expected to stay behind the walls of a cloister. Instead, they traveled among the people, taking as their example the Cathars who emulated tthe apostles of the primitive Church. Dominic Guzmán's new order was to be a preaching order, trained to preach in local languages - again copying the Cathars who preached in Occitan. Rather than earning their living, Dominican friars would survive by begging, "selling" themselves through persuasive preaching.

They were both active in preaching, and contemplative in study, prayer and meditation. As today, the Brothers preached while the Sisters prayed for the the success of the Brothers' teaching.

In the spring of 1203, Dominic Guzmán joined Prior Diego de Acebo on an embassy to Denmark for the monarchy of Spain, to arrange the marriage between the son of King Alfonso VIII of Castile and a niece of King Valdemar II of Denmark. At that time the Languedoc was the stronghold of the Cathar or Albigensian belief,

Prior Diego saw immediately one of the paramount reasons for the spread of Catharism: the representatives of the Holy Church lived openly with an offensive amount of pomp and ceremony. On the other hand, the Cathars lived in a state of self-sacrifice that was widely appealing. For these reasons, Prior Diego suggested that the papal legates begin to live a reformed Cathar style (ie apostolic) life. The prior and Dominic Guzmán dedicated themselves to the (largely unsuccessful) conversion of the Cathars

According to legend, Dominic Guzmán became the spiritual father to nine women he had reconciled to the Catholic faith, by miraculously facing down a demonic black cat in the church at Fanjeaux. In later traditions they would become Cathar Perfects converted by his convincing arguments. In 1206 the alleged converts were established them in a convent in Prouille, near Fanjeaux. This convent would become the foundation of the Dominican nuns, and later become Dominic Guzmán's headquarters for his missionary efforts in the Lauragais.

Prior Diego died, after two years in the mission, on his return trip to Spain, leaving Dominic Guzmán to develop his new Order. Guzmán established a religious community in Toulouse in 1214, to be governed by the rule of St Augustine and statutes to govern the life of the friars, including the Primitive Constitution. (The statutes borrowed from the Constitutions of Prémontré.) Founding documents establish that the Order was created for two purposes: preaching and the salvation of souls.

In July 1215, with the approbation of Bishop Foulques of Toulouse, Dominic Guzmán ordered his followers into an institutional life. Friars were organized and trained in religious studies. The Rule of St Augustine was an obvious choice for the Dominican Order, Like Augustinians, Dominicans were to be not monks, but canons-regular. They could practice ministry and common life.

The Order of Preachers was approved in December 1216 and January 1217 by Pope Honorius III in the papal bulls Religiosam vitam and Nos attendentes. On January 21, 1217 Honorious issued the bull Gratiarum omnium recognizing Dominic Guzmán's followers as an Order dedicated to study and universally authorized to preach, a power formerly reserved to local episcopal authorization.

On August 15, 1217 Dominic dispatched seven of his followers to the university center of Paris to establish a priory focused on study and preaching. The Convent of St. Jacques, would eventually become the Order's first studium generale. Dominic Guzmán was to establish similar foundations at other university towns of the day, Bologna in 1218, Palencia and Montpellier in 1220, and Oxford just before his death in 1221.

In 1219 Pope Honorius III invited Dominic Guzmán and his companions to take up residence at the ancient Roman basilica of Santa Sabina, which they did by early 1220.

The order developed rapidly into Inquisitors in Carcassonne, Toulouse and Albi, a position regularised by later popes. Dominicans were formally appointed by Pope Gregory IX to conduct the Papal Inquisition. In his Bull Ad extirpanda of 1252, Pope Innocent IV authorised the Dominicans' use of torture.

|

The site of one of many miracles allegedly performed by Dominic Guzman. |

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By Saint

Dominic de Guzmán (1475); Pedro Berruguete (around

1450-1504) commissioned by Torquemada, Oil on wood . 60 5/8

x 36 1/4 (154 x 92 cm). |

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By Saint

Dominic de Guzmán (1475); Pedro Berruguete (around

1450-1504) commissioned by Torquemada, Oil on wood . 60 5/8

x 36 1/4 (154 x 92 cm). |

|

|

Dominicans copied many aspects of Cathar practice, including the wearing of black outer rober |

|

|

Dominic

Guzmán was a proponent of the scourge or "discipline"

to mortify the flesh. Here he is flagellating himself with

iron chains. |

|

Franciscans

The Franciscans played a relatively small role in the events of the medieval Languedoc. A few Franciscan Inquisitors supplemented the Dominican Inquisitors, apparently to soften their harshness and reduce their extensive corruption. Perhaps the most notable role played was that of Bernard Délicieux (c. 1260-1270 – 1320), a Spiritual Franciscan friar who resisted the Inquisition in the Languedoc.

Bernard Délicieux

Born in Montpellier, France sometime in 1260-1270, Délicieux joined the Franciscan Order in 1284 and worked in Paris before the 1299. Around 1299, Délicieux became prior of the Franciscan convent in Carcassonne where he led a revolt against the city's oppressive Inquisitors, preventing the arrest of two alleged Cathars who were given sanctuary in the Franciscan convent.

In July 1300, Délicieux appealed the accusation that Castel Fabre, deceased in 1278 and buried at the Franciscan convent, had been a heretic. Délicieux claimed the Inquisition registers were fraudulent and contained accusations from non-existent informants. This incident caused the Inquisitors to temporarily flee Carcassonne.

In 1301, Délicieux befriended the newly appointed viceregent of Languedoc, Jean de Picquigny. Together, they visited King Philip The Fair in October and argued that Carcassonne Inquisitor Foulques de Saint-Georges and Bishop Castanet were corrupt and abused their power, and thereby endangered loyalty to the French King. As a result, friar Foulques was reassigned and support from royal constables to arrest subjects suspected of heresy was reduced. Bishop Castanet was fined 20,000 livres and had his temporal authority restricted.

Around. 1302, Délicieux was transferred from Carcassonne to the Franciscan convent in Narbonne. He travelled extensively throughout Languedoc preaching. In the spring, a second visit to the royal court failed to secure the release of Inquisition prisoners held in Albi and Carcassonne.

In 1303, Délicieux returned to Carcassonne and pressured to reveal the secret accord of 1299, which reversed Carcassonne's earlier excommunication in 1297 by the Inquisitor Nicholas d'Abbeville. On August 4, 1303, Délicieux gave a fiery sermon and claimed the 1299 accord admitted people of Carcassonne were (reformed) heretics and, hence, liable to be burned at the stake if they found to have relapsed.:120–121 The following week, the Inquisitor Geoffroy d'Ablis tried to dispel the accusations that the accord was unfair for Carcassonne, but a riot ensued:128 Based upon encouragement from Délicieux and to reduce tensions between the townsfolk and the Inquisitors, Jean de Picquigny, backed by royal troops, forcibly transferred the prisoners from Inquisitor's jail to the more humane royal jail.

In January 1304, Délicieux and Picquigny met with King Philip The Fair in Toulouse along with Dominican and other church officials as well as town representatives from Carcassonne and Albi. Délicieux angered the King by suggesting he was a foreign occupier of Languedoc. Consequently, there was no policy change and the Inquisition would continue under oversight from local bishops.

In the spring of 1304, Délicieux travelled to Kingdom of Majorca to encourage Prince Ferran to back a revolt in Languedoc as an alternate ruler. However, King Jaume, an ally of King Philip, learned of the plot and ejected Délicieux from his kingdom.

On April 16, 1304, Pope Benedict XI wrote a bull Ea nobis ordering the Franciscans to arrest Délicieux for "saying such things as we must not". The instruction was unfulfilled due to Benedict XI's death.

Délicieux's succession plot was uncovered by royal authorities in the fall of 1304 and he travelled to Paris to attempt to gain an audience with King Philip IV. In Paris, Délicieux was placed under house arrest, but otherwise unpunished.

After the election of Pope Clement V in 1305, Délicieux was transferred to the papal authority, where he formed part of the Pope's entourage that ultimately moved to Avignon in 1309. Shortly thereafter (c. 1310), Délicieux was released and joined the Spiritual Franciscan convent in Béziers.

In April 1317, Pope John XXII ordered the Spiritual Francisions from Béziers and Narbonne, including Délicieux, to come to Avignon and answer for their alleged disobedience. Upon arrival, Délicieux was arrested. Over the next year, he was interrogated and tortured. Bernard de Castanet created forty charges, later expanded to sixty-four charged by the Dominican Inquisitor Bernard Gui. The charges against Délicieux were:

- Disobeying the Franciscan Order as a Spiritual

- Treason against the French King

- Murdering Pope Benedict XI

- Obstructing the Inquisition

Délicieux was transferred from Avignon to Carcassonne for his trial, which ran from September 12 to December 8, 1319. The judges and prosecutors were Jacques Fournier, the Bishop of Pamiers (future Pope Benedict XII), and Raimond de Mostuéjouls, the Bishop of St. Papoul.

Following torture and threat of excommunication, Délicieux confessed to the charge of obstructing the Inquisition. Délicieux was also found guilty of treason, but not guilty of murdering Pope Benedict XI. No verdict was given for being a Spiritual Franciscan, the original reason for his arrest in Avignon. As punishment, Délicieux was defrocked and sentenced to life in prison in solitary confinement. The judges sentencing Délicieux ordered that his penance of chains, bread and water be omitted in view of his frailty, age and prior torture, Pope XXII countermanded their order and delivered the friar to Inquisitor Jean de Beaune. Serving this harsh sentence, Délicieux died shortly thereafter in early 1320.

|

Modern Franciscans |

|

|

|

|

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921) (Showing Bernard Délicieux releasing prisoners of the Dominican Inquisition) |

|

|

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921) (Showing Bernard Délicieux speaking out against Inquisition abuses) |

|

Cathar views of Catholics and Catholicism

Before the persecutions started, Cathars seem to have regarded the Roman Church much the same as everything else in this material world. But increasingly evidence seemed to confirm that the Roman Church was actively allied to the wrong God. In the first place the Roman Catholics venerated the Old Testament. But the God of the Old Testament was not the Good God that Cathars recognised. He was, as anyone can confirm themselves by reading the Old Testament, ignorant, cruel, bloodthirsty and unjust. For Cathars the God of the Old Testament was the Demiurge, the supernatural being that we associate with the Devil. In other words, for the Cathars, Roman Catholics were voluntarily worshipping Satan.

Other Catholic beliefs and practices seemed to provide confirmation. Anyone who attached great value to material things was at best mistaken and at worst a disciple of the Bad God, and here again the Roman Church seemed to qualify. Cardinals, bishops and priests lived in great luxury and dressed in gorgeous robes. Even Churchmen recognised the fault of their fellow shepherds. Pope Innocent III, the richest man in Christendom, noted of the Archbishop of Narbonne:

"…He knows no other god but money and has a purse where his heart should be. His monks and canons take mistresses and live by usury… Throughout the region the prelates are the laughing stock of the laity."

Cathars knew their scripture and could cite Matthew 7:22

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate one and love the other; or else he will hold to one and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and Mammon.

Further, the Roman Church encouraged the worship of material objects such as the relics of saints. And worse yet it venerated the cross - not only a material object but also an instrument of torture. All this seemed to confirm that Roman Catholics were worshipping the God of Evil who had created this world. That the Roman Church perverted Christian Scripture, replaced ancient rites with new ones, and persecuted minorities provided yet more confirmation. They drew what seemed obvious conclusions from Matthew 7, 15-16:

Watch out for the false prophets who come to you in the guise of lambs, when within lurk voracious wolves. Only their fruit will tell them apart.

So it was that Cathars referred to the Roman Church as the Church of Wolves.

|

The Whore of Babylon (which Cathars identified as the Roman Catholic Church) riding a seven headed beast |

|

Catholic Views of Cathars and Catharism

Almost all modern historians are sympathetic to the Cathars. Even the most scholarly and objective works, laying out the bare facts as fairly as possible come across as sympathetic. Here is a quote from what is generally regarded as the best English language academic work of the twentieth century, referring to the Cathars:

|

|

and again

|

|

Even the better quality contemporary medieval opponents recognised their merits. Here is James Capelli, a friar who was lector at a Franciscan convent at Milan writing around 1240. As Wakefield and Evans say, he "displays scruples rarely encountered in other authors of polemical tracts"

|

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda

This is not how the Roman Catholic Church sees the Cathars and

their "heresy". The Church's modern views, expressed by

writers like Hilaire Belloc, and are not very different from those

of the Medieval Roman Catholic Church (see Hilaire

Belloc, The Albigensian Attack, Chapter Five of The Great

Heresies  )

)

To most objective authorities the more serious accusations against the Cathars appear to be based on no more than propaganda. No organisation has ever used propaganda to such good effect as the Roman Church. The very word propaganda is derived from the name of the part of the Roman Church set up to propagate the faith. For many centuries the Catholic Church provided a set-menu of accusations against any group of which it did not approve: pagans, Eastern Churches, apostates, schismatics, heretics, Jews, Moslems, witches, Templars, numerous peoples of the New World, and so on. They were all accused of black magic, worshipping Satan, consorting with demons, aping Catholic rituals, murder, cannibalism, incest, bestiality, sodomy and a range of sexual excesses. Cathars were no exception. All of the preceding accusations were made against them, however scant or contrary the evidence.

|

An example of the contrast between propaganda and truth is provided by the disparity between alleged and real attitudes to sex. According to Catholic propaganda, Cathars including Parfaits and Parfaites habitually engaged in sexual excesses, including regular orgies. At the same time as propagating these calumnies the Catholic Church authorities were detecting heretics not by their sexual excesses but by their sexual purity. We have a striking example from the twelfth century in the Archdiocese of Rheims where a group of heretics ("Poblicani") were discovered through the refusal of a young girl to submit to the attentions of a clergyman. The refusal of a girl to submit to a clergyman's sexual demands appears to have been so unusual that she was questioned and admitted that she believed she had an obligation to keep her virginity. As a result, she and her friends were investigated more closely and soon a nest of heretical believers was exposed. The heretics were described by the Archbishop, Samson, who asserted that heresy was being spread by itinerant weavers who encouraged sexual promiscuity. |

|

The Roman Church accused Cathars of various crimes and sins. These claims ranged from the true to the preposterous. Here we untangle them. Each of the following charges is dealt with separately:

- Claims of Cathar "blasphemies"

- Claims that Cathars rejected marriage

- Claims that Cathars practised incest

- Claims that Cathars practised

sodomy

- Claims that Cathars practised bestiality

- Claims that Cathars practised other

sex crimes

- Claims that Cathars practised

suicide

- Claims that Cathars practised contraception

- Claims that Cathars practised vegetarianism

- Claims that Cathars advocated sexual

equality

- Claims that Cathars perverted

the natural order

|

Dominic Guzmán (with a halo), Arnaud Amaury, and other Cistercian abbots crush helpless Cathars underfoot - a sanitised version of the persecution of the Cathars |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Blasphemy

A Sexual Retainship Between Jesus and Mary Magdelene?

An intriguing accusation made against the Cathars was that they taught that Jesus and Mary Magdelene had engaged in a sexual relationship. It is difficult to know if this was just propaganda. On the one hand it hardly matches the Cathar view that Jesus was a divine phantom. On the other hand there does seem to have been a school of Gnostic Dualist thought that there were two Jesus Christs - one divine and good, the other earthly and bad. Cathars could well have believed that the bad earthly Jesus had married.

Also this was an accusation made frequently in the very earliest years of Christianity and it is consistent with other hints. Early Gnostic gospels have Mary ranking above the "other apostles" and one refers to Jesus kissing Mary on the .... (tragically, there is a gap in the manuscript here, but most scholars slot in the word "mouth" as a best guess). In any case the accusation concerning a sexual relationship is not an invention of modern fiction writers as is sometimes claimed. The accusation appears in works by thirteenth century Inquisitors and Church chroniclers. Here is one example from a Cistercian Monk:

Further, in their secret meetings they said that Christ who was born in the earthly and visible Bethlehem and crucified at Jerusalem was evil, and that Mary Magdelene was his concubine - and that she was the woman taken in adultery who is referred to in the scriptures [John 8:3]

Peter des Vaux-de-Cernay, Historia Albigensis (In WA & MD Sibly's translation into English (Boydell, 2002) at {11} p 11). The accusation is repeated at {91} p51. Incidentally the Roman Catholic Church later adopted the Cathars' identification of Mary Magdelene with the woman taken in adultery (hence for example terms such as "the Magdelene Sisters")

According to some authorities the Cathars believed that Mary Magdelene was not merely Jesus's concubine, but had been married to him. As Durand de Huesca tells us, writing between 1208 and 1213:

Also they teach in their secret meetings that Mary Magdelene was the wife of Christ. She was the Samaritan woman to whom he said "Call thy husband" [John 4:16]. She was the woman taken in adultary, whom Christ set free lest the Jews stone her, and she was with Him in three places, in the temple, at the well, and in the garden [cf John 8:3-11].

This English translation (with my square brackets) is from Wakefield and Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, p 231, and based on the text printed by Antoine Dondaine "Durand de Huesca et la polemique anti-cathare" Archivum fratrum praedicatorum, XXIX (1959) 268-71.

|

The close relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdelene is reflected in traditional Christian art. |

|

|

The close relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdelene is reflected in some traditional Christian art. |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda:

Cathar Views on Marriage

One of the claims of the Catholic Church was that Cathars rejected marriage. Since God had enjoined marriage, it must be sinful, and heretical to reject it.

There was some truth to the underlying charge. Cathar teaching was that procreation enslaved more angels in human bodies. It followed that procreation was bad. In Catholic thought one of the three explicit purposes of marriage was procreation (In Cannon Law people who could not procreate. Eunuchs for example were - and still are - disbarred from marrying). If procreation was undesirable for Cathars then marriage must be undesirable too. The reasoning held in some respects, but failed to accommodate nuances and qualifications.

The first is the Cathar concept of marriage, which was very different from our modern idea of marriage. For Cathars the word denoted not a ceremony joining a man and a woman, but a ceremony joining the entrapped human soul with its spiritual body in heaven. This was one of the functions of the Cathar ceremony called the Consolamentum, a ceremony preserved from the earliest days of Christianity, from which the various Orthodox Mysteries and Catholic Sacrament evolved over the centuries. This interpretation enabled Cathars to read and interpret the New Testament without discomfort, since references to marriage could be interpreted as referring to this "Spiritual Marriage."

The Second qualification is that in Cathar thought the horror of sex and reproduction applied principally to Parfaits (men) and Parfaites (women). Ordinary believers or credentes were not expected to remain chaste, though it would be desirable if they did so. There appears to have been no stigma associated with marriage between ordinary believers and it is known that many believers did marry and raise families. In this, the practice of the Cathars again represented a preservation of the earliest Christian practices, where Virginity was the ideal and marriage was an acceptable second best (As Paul put it: "It is better to marry than to burn"). Virginity could be combined with a form of spiritual marriage. In different ways both Cathars and Catholics retained the idea. Virginity and chastity for Cathars was associated with their spiritual interpretation of marriage. Virginity and chastity for Catholics was associated with a different form of spiritual marriage. Monks were thought to marry the Church on their induction. Nuns were thought to marry Christ (In some orders they are known as "Brides of Christ". They still don wedding dresses, wedding crowns and even wedding rings on their inception).

Another ancient practice preserved in different ways was that of becoming celibate after having been married. This was extremely common practice - indeed standard practice - in the Early Christian Church, just as it remained standard among Cathars. It was for example very common for noblewomen with Cathar sympathies to marry and raise families and then, with their husband's consent, to begin an ascetic life culminating in taking the Consolamentum and so joining the ranks of the Parfaites. This too had a parallel in the Catholic Church, where it was common for men to abandon their wives in order to become monks or priests (Folque of Toulouse is just one of innumerable examples from the thirteenth century). Similarly, Catholic noblemen often packed their unwanted wives off to nunneries. In both cases the Church regarded the original marriage as dissolved so that the person could remarry either the female Church or the male Christ, according to gender. Related to this practice is the apparent anomaly that although a Catholic priest may not marry, the Church has no ban on married men becoming priests, as many have done and still do today.

From all the evidence, no Cathar seems to have been undully exercised by the fact that believers married and raised families. How else could those awaiting reincarnation ever be freed from their cycle of imprisonment?

Even so, the simplistic interpretation by which Cathars should abhor marriage seems to have some practical implications. For example it seems to have provided a strand of argument for propagandists. According to them all Cathars rejected marriage and were therefore heretics. The propagandists appear to have fudged the distiction between believers and Parfaits, and presented the rejection of marriage as an horrific heresy in itself. The audience were unlikely to know that virginity was such an ideal in the earliest Church, and the propagandists could hardly admit that the real Cathar practice of chastity represented represented exactly the ideal of chastity that monks aspired to or the ideal of celibacy that priests aspired to.

Anyone who believed the propaganda could deduce that Cathars would not marry and that anyone who was married could not therefore be a Cathar. Although the reasoning is flawed on two different counts, it does seem to have been articulated as an argument by people accused of being Cathars by the Inquisition. Here is a revealing appeal by one Jean Teisseire accused of heresy:

|

|

|

It did not save him. Further enquiries were made. Teisseire was burned alive and his wife condemned to perpetual imprisonment.

|

Jesus putting a wedding ring on the finger of his new (Catholic) bride |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Incest

There is no evidence that Cathars were given to practice incest.

The accusation probably stems from the observation that the Cathars regarded all procreative sex as equally bad. So, Catholic theologians reasoned, Cathars must regard sex between man and wife as being as sinful as sex between man and mother (true) and they they must have practiced the later (false).

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Sodomy.

There is no evidence that Cathars were given to practice sodomy.

The accusation probably stems from the observation that the Cathars regarded procreative sex as worse than non-procreative sex. So, Catholic theologians reasoned, Cathars must regard sodomy as being less culpable than conventional sex (true) and they must have practiced the former (false).

This was an effective and persistent accusation. Remember that Cathars were given many names. When they first appeared in Western Europe they were known to have come from the area be know as Bulgaria. They were thus called Bulgres, a word that Church propaganda turned into French Bougre and English Bugger.

Ironically, sodomy has always been widely practiced in the Catholic Church, though never formally condoned. Various church orders were famous for it - Voltaire was particularly fond of ribbing the Jesuits about how widespread it was in their Order. And it was not only practised between Catholic men - anal sex was commonly practiced in Catholic countries between man and wife as a means of contraception.

Since Cathars had no moral objection to other forms of contraception it seems likely that, on average, Cathars would have had less need for recourse to this practice as a means of contraception, so it is possible that they practised sodomy rather less than their Catholic counterparts.

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Bestiality.

There is no evidence that Cathars were given to practice Bestiality.

The accusation is based on the idea that heretics were interested in, and given to kissing, the backside of cats. There seems to be no genuine evidence for this practice, nor any plausible explanation of how the accusation arose. One Catholic Authority, writing about 1182, tells us about "many" reformed Cathars who admitted that at night groups of heretics :

|

|

|

It is notable that such accusations were made against other groups that the Roman Church regarded as its enemies. For example, the same accusation was used a century later against the Knights Templars and then against supposed witches. One factor is that Catholics imagined that the devil liked to adopt the form of a cat - which also explains why cats are still associated with witches in the mainstream Christian mind.

The most likely explanation seems to be the fevered imagination of some unknown medieval churchman. All it would take was one deranged Episcopal Inquisitor plagued by fantasies of the feline podex. Such an Inquisitor could extract whatever confession he wanted from anyone who came into his power. The confession would then establish an accepted view of how heretics and the devil operated. This could be confirmed by any number of further confessions extracted under torture or duress. Positive feedback loops like this proved any number of unlikely accusations - sailing in sieves, flying through the air, taking animal form, demonic visitations, and so on.

The name Cathar may be derived from a German word referring to this particular calumny about cats' backsides, but it rather backfired when everyone assumed that the name must come from the Greek word for pure.

|

Thirteenth century Miniature from the Bible Moralisée, Bibliotèque Nationale de France. On the right of the illustration, the devil in the form of a cat is climbing down his pole |

|

|

Devil and the cat worshippers kissing the cat’s backside Jean Tinctor, Traittié du crisme de vauderie (Sermo contra sectam vaudensium), Bruges ca. 1470-1480 (Paris, BnF, Français 961, fol. 1r) |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Contraception

In line with St Augustine's views of proper functions for each organ of the body, Catholics abhored contraception. In contrast, Cathars despising all things physical and especially reproduction, found contraception perfectly acceptable.

The theory is simple, but the practice more complicated. There is some evidence that Cathars practiced contraception, but it is difficult to know if they practiced it more than their Catholic neighbours.

The best documented case of contraception being used comes from the Inquisition's records of the interogation in 1320 of a suspected Cathar, Béatrice de Planissolles, and her lover, by the Inquisitor-bishop Jacques Fournier. Unfortunately the picture is clouded by the fact that the lover was also a Catholic priest - the curé at the famous village of Montaillou.

Click on the following link to read Beatric's testimony concerning

her

and her lover priest's favoured methods of contraception

Click on the following link for more information about the events at Montaillou

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Sexual Equality

The idea of women having power over men was hateful to the Roman Church, relying on an injunction by St Paul that women should have no dominion over men, and a number of similar biblical assertions. Soon after it had developed a priesthood in the early centuries, the Orthodox Church (from which the Roman Church would later split off), started to minimalise the role of women. They were barred from the new priesthood, and prominant women in the bible were concealed by a simple name change (eg Julia "who was prominent among the disciples" became Julian). Deaconesses disappeared later, and later still women were even excluded from choirs. By the Middle Ages the role of women in the early Church had been forgotten, and St Paul said everything on the matter that was needed. From this perspective, it seemed anti-Christian to allow any form of equality to women. Churchmen were horrified therefore to learn that Cathars had not only Parfaits (male members of the elect) but also Parfaites (women members of the elect). This was probably exacerbated by misunderstandings - for example Catholics never seem to have understood that Cathars did not recognise a priesthood, nor did they understand the nature of the Melhoramentum.. In their minds women Parfaites were priestesses, worshipped by ordinary believers. The truth would have been bad enough, but this seemed to be an even more pernicious blasphemy.

Although the Waldensians were doctrinally as opposed to the Cathars as the Catholic Church, they nevertheless adopted some Cathar ideas, for example permitting women a role in spreading the faith. Here is the Cistercian Alan of Lille writing against this heretical idea around 1190-1202:

|

|

Times change, and equality of women is now regarded as laudible outside the Roman Church. There is therefore a danger of misreprenting Parfaites as being fully equal to Parfaits. The truth is not quite so straightforward. Certainly, Parfaites underwent the same training as Parfaits. They took the same vows at identical ceremonies. They led the same ascetic lives, and probably enjoyed the same rights at least in theory. In practice Parfaites do not seem to have travelled and preached, nor did they normally administer the Consolamentum, nor do they seem to have been elected as bishops. Instead they lived together in communities, often in large town houses.

|

In summary, neither the propaganda of the Roman Church nor the rosy picture of the Cathar apologists is right, but both are near the truth, which is that women treated much more like the equals of men than they were in the Medieval Church (or in the modern Roman Church). It is possible that the Cathars treated women in the same way that the earlist Gnostic Christians had treated women - initially unaware of St Paul because they predated him, and later ignoring his innovative opinions. |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda:

Other Sex Crimes

A Christian principle, adopted by St Augustine from the ancient Greeks, it that every part of nature has a proper function. This reasonable sounding proposition can be extended to a less reasonable conclusion: that every part of nature, and in particular every part of the human body, should be used for its proper function and for nothing else. This idea was still familiar to Christian believers into the twentieth century, generally to justify prohibition: If God had meant you to smoke, he would have given you a chimney. If God had intended you to swim, he would have given you fins. If God had intended you to fly, he would have given you wings. This sort of argument has largely been abandoned (applying it consistently takes theologians where they prefer not to go). But there is one example of this idea that is still applied almost as strongly as it was in the time of the Cathars. God had designed the sex organs for the purpose of reproduction, so it was and is wrong to use them for anything else. In particular it was, and is, of the utmost importance that semen should should be deposited in a human vagina. Every sperm is sacred.

This idea explained many aspects of Catholic theology which seem odd to outsiders. Not only did it justify bans on sodomy and contraception, but also coitus interuptus and masturbation. On this question, Cathars held almost exactly the opposite view. While Catholics taught that semen should be deposited where it could lead to conception, Cathars held that semen could be deposited anywhere that it could not lead to conception. So it was that on one hand practices like masturbation could be no sin whatsoever to Cathars, and why on the other Catholics could believe it to be a heinous crime against God. Who practised it more is a different question, and one to which we do not know the answer. (Catholic teachings following the traditional line of argument have now been abandoned, or at least are no longer openly advocated. For example, as we know from medieval penitentials, experiencing a nocturnal emission was a far more serious sin than committing rape. The former involved spilling seed outside its divinely appointed receptacle, and the latter involved depositing it in the correct receptacle. The former therefore was a serious sin, and the latter was not.)

Roman Catholic Propaganda: Vegetarianism.

This is one charge that is undeniable.

Cathars, or at least Parfaits and trainee Parfaits, refused to eat animal products - not only meat but also milk, cheese and eggs - anything that resulted from coition. Some at least refused to eat honey, apparently on the grounds that it, like the morning dew, was the product of monthly copulation between the sun and the moon

In many respects Cathar parfaits resembled modern day vegans, except that they did eat fish. (The justification was that fish, as they believed, did not reproduce sexually and so could not imprison a soul as other animals could). That fish reproduced asexually was a genuine and widespread belief in the Middle Ages. The same error underlay the Catholic practice of eating fish on fast days. This practice is still alive in the Roman Church, and a vestige of the same error is the common practice of serving fish on Fridays - Fridays having been traditional fast days. Incidentally, the Roman Church classified such diverse animals as beavers and barnacle geese as fish with the happy consequence that their fast day diets were not as boring as they might otherwise have been. Another such wheeze was to eat animal embryos, on the grounds that they lived in water (the fluid within the womb) and so also counted as fish. Inexplicably, but happily, the logic does not seem to have been applied to human fetuses

For many centuries the Roman Church regarded vegetarianism as a capital crime on the grounds that God had given man dominion over the earth and had provided animals for him to eat. Inquisition records include cases of people being required to kill and eat animals, often chickens, to prove that they were not Cathars. Failure to do so meant death.

The Mainstream Church was hostile to vegetarianism well into the twentieth century. In Britain a Government Minister, John Selwyn Gummer, could still publicly ridicule vegetarians as being anti-Christian as late as the 1980s, citing the traditional argument that God had given man dominion over the earth and had provided animals for him to eat.

Vegetarians are still regarded as vaguely anti-Christian by many denominations even today.

|

|

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda:

Perverting the Natural Order

To the conventional Roman Catholic mind, human society is planned and ordered by God. God has ordained what is natural and what is not. The problem arises when we need to distinguish between what is natural and what is not. If we look to evolution or to human nature, we do not always arrive at the same results as the Medieval Church. To an objective outsider it looks as though the Medieval Church hierarchy used its own cultural preconceptions to distinguish between natural and unnatural. Broadly, anything the Church agreed with was natural, and anything the Church disagreed with was unnatural. Under these rules the Church and everything it stood for were natural, and anything opposed to the Church was unnatural.

This outlook explains the enmity of the Roman Church to many aspects of the Cathars. For the Roman Church their views were orthodox, other views were heretical. Their ideas on sex were right, other views were perverse. Their views on women were God-given, other views were blasphemous. Their religious rites and books were divine, others were vile satanic parodies. So too for ideas about suicide and meat eating.

For Medieval Catholics the feudal system was part of the natural order no less than the priesthood. Everyone was born to a particular station in life - the idea of monarchs reigning "by the Grace of God" was to be taken literally. Catholic Churchmen were horrified to find that in Cathar lands little value was placed on the feudal system, and the natural order seemed to be inverted. A knight might bow down to a Parfait who was an ordinary commoner. In theory it could be even worse: a Count might bow to a Parfaite.

Perhaps the best illustration of how easily current fashion was

mistaken for the natural God-given order is provided by attitudes

to biblical injunctions. Catholics were horrified that Cathars

would not swear oaths, and were not in slightest moved by the fact

that the bible says clearly and repeatedly that oaths must not be

sworn - the feudal system and Church courts relied on ignoring this

part of scripture. Again, Catholics were mystified by the Cathars

refusal to kill. Catholics took it granted that it was God's

will that they should kill almost anyone or anything they wanted

to (Click on the following link for more about ignoring

biblical injunctions ).

).

|

The three estates appointed by God: cleric, knight and peasant. British Library; Manuscript number: Sloane 2435, f.85 |

|

Roman Catholic Propaganda:

Suicide & Euthenasia

The Roman Church regarded suicide as a mortal sin. It therefore made much of this heinous crime.

For Cathars, there was no reason to regard suicide as a sin. According to their theology, death represented an opportunity for the soul to escape this early hell and return to the realm of light. They apparently did not regard the Commandment "Thou shalt not kill" as applying to suicide.

Theoretical acceptance does not imply, as some Catholic authors still suggest, that suicide was common. We know that ordinary believers led fairly ordinary lives, almost in spite of their theology - they married, copulated, raised and cared for their families much like anyone else. The Cathar practice was probably much the same as the one accepted by educated people in classical times and by the overwhelming majority of secular thinkers today. Greeks, Romans, Cathars and Humanists could all condone suicide, finding no moral objection to it, without manifesting any inclination to practise it themselves.

Some Cathars are known to have undertaken the Endura, a form of voluntary euthenasia, generally in anticipation of imminent death. Similarly, believers who were mortally wounded might take the Consolamentum and then simply refuse to eat or drink. In this they saved themselves unimaginable suffering and, as they believed, won their place in heaven.

Oddly, There is no record (as far as I know) of Cathars captured by the Inquisition choosing to undertake the Endura. Catholic propaganda might have been expected to make much of such heinous self-murder - it could easily have fabricated suicide stories (as some modern Catholic writers do) - but it did not. Why not?

Kill Them All ...

In recent times some people have started to voice doubts about whether Arnaud Amaury ever spoke the words attributed to him and this has become a point of contention between Catholic apologists and others. Below is a summary of the relevant arguments and sources:

| Reasons to doubt that Arnaud Amaury spoke the words "Kill them all…" | Reasons to believe that Arnaud Amaury did speak the words "Kill them all…" | ||||||

| The words are too appalling to have been spoken by any senior churchman. |

The words are consistent with the recorded statements of contemporary senior churchmen, many of whom also led armies. Such leaders often talked about extirpation or extermination, and were responsible for numerous mass slaughters. Like almost all of their statements justifying killing in general and genocide in particular, this one is grounded in scripture. The words are based on a citation from 2 Tim. 2:19: "... The Lord knoweth them that are his. ...". To take another example, here is an extract from the The Song of the Cathar Wars [Canso, laisse 214] recording threats made by Bertrand, a Cardinal of Rome concerning the siege of Toulouse (1216-1218) less than a decade after the massacre at Béziers (this threat is based on Old Testament passages commending genocides):

The principal was not restricted to Crusade leaders, and was articulated by other Churchmen. The Bolognese legal scholar Johannes Teutonicus wrote in 1217 (around the same time as the above) in a commentary on Gratian: "If it can be shown that some heretics are in a city then all of the inhabitants can be burnt" [Johannes Teutonicus, Glossa ordinaria to Gratian's Decretum, edited by Augustin and Prosper Caravita (Venice, Apud iuntas, 1605), C 23, q 5, c32 - cited by Mark Pegg, A Most Holy War, OUP, 2008, p 77] |

||||||

| Such a concept is fundamentally un-Christian |

|

||||||

| There is no reason to think Arnaud Amaury would plan a massacre like this - it could have been carried out by a rabble of crusaders. |

The massacre is consistent with contemporary and sympathetic records of the Crusaders' strategy. According to the Canso, [laisse 5] Innocent III, Arnaud, Milo and 12 cardinals planned their strategy in Rome in early 1208:

Again, according to the Canso, laisse 21, the Crusader Army under Arnaud's command confirmed plans for mass slaughters, exactly like this one, immediately before the siege at Béziers.

and the reasoning behind this is explicit:

Yet again, no fewer than three separate sources tell us that Renaud de Montpeyroux, the Bishop of Béziers, having consulted with the Crusaders, indicated to the citizens that their blood would be on their heads if they did not surrender the town and hand over their Cathar neighbours. (Canso 16-17, Historia albigensis §89, and a letter to Innocent III from Arnaud and Milo referred to below). Here is the Canso's version:

As WA and MD Sibly point out "These accounts suggest that at this stage the crusaders did not intend to spare those who resisted them, and the slaughter at Béziers was consistent with this" (WA and MD Sibly, The History of the Albigensian Crusade, Appendix B, p 292) |

||||||

| This sort of brutality is inconsistent with the commandment "Thou shalt not kill". |

Arnaud Amaury promoted this crusade specifically to kill. The whole point of any Crusade was Holy War - in which the enemy are killed. Raymond-Roger Trencavel, Viscount Béziers had already offered his submission before the siege started - so the Crusaders could easily have avoided bloodshed if they had wanted to. The words "Kill them all ..." are consistent with everything we know about the character and record of Arnaud Amaury, who seems to have taken every opportunity to maximise the death toll among those he regarded as his enemies. After the famously brutal Simon de Montfort was appointed to take over military command of the Crusaders, Arnaud Amaury as papal legate occasionally overruled him, demanding more punitive action than Simon favoured, as for example at Minerve. As one historian explains "Extraordinary holiness and extraordinary cruelty were never incompatible during the crusade - indeed, more often than not, they went together by necessity. The redeeming majesty of His love was revealed only through wholesale slaughter honouring Him. (Mark Pegg, A Most Holy War, OUP, 2008, p 161). It is also significant that in all of the contemporaty records and comentaries, not a single Catholic writer records a hint of regret for the massacre. On the contrary it is lauded as just and divinely inspired. This is in itself evidence that such an attrocity was regarded as a perfectly normal event for holy Crusaders. |

||||||

| The words were not recorded during the actual event, but some years later. (Some apologists claim a time lag of over 60 years) |

The words "Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius" are first recorded (with approval) by a fellow Cistercian chronicler, Caesarius of Heisterbach (c1180-1250) in his work on miracles (Caesarius Heiserbacencis monachi ordinis Cisterciensis, Dialogus miraculorum, ed. J. Strange, Cologne, 1851, J. M. Heberle, Vol 2 , 296-8). The exact time lag from the even to it being first recorded is not known for certain, and may have been a few weeks or months. In any case it cannot be more than 40 years since Caesarius died in 1250. So at the worst, the time lag would be comparable to that between Jesus' lifetime and the writing of the gospels. It not obvious why different standards should be applied - so that the time lag is of no consequence in one case but fatal in the other. Caesarius was an adult at the critical time, 1209, and would have had personal contact with Crusaders and especially with fellow Cistercians who had taken part in the Albigensian Crusade. Furthermore he seems to be well informed - he says nothing that contradicts the known facts from several different authoritative sources and supplies convincing additional detail as to how the besiegers managed to breach the city's defenses. At the beginning of Chapter XXI of his work, he says "In the time of pope Innocent, the predecessor of the present pope, Honorius, ...". For him to be able to write this Honorious III (the successor of Innocent III) must have still been alive. Honorius died on 18th March, 1227 which means that Caesarius could not be writing more than twenty years after the massacre at Béziers. If we discount the reliability of this account on the grounds of possible time delay, then we would need to discount most medieval chronicles on the same grounds. The text gives other clues - for example that Raymond VI of Toulouse was still alive at the time of writing. (He died in 1223). Again, Cardinal Bishop Conrad was a papal legate against the Cathars at the time, which pins it down to 1220 - 1223, at most fifteen years after the massacre at Béziers. In fact we know that Caesarius wrote his Book on Miracles between 1221 and 1223 - confirming that the story was published at most fifteen years after the massacre at Béziers - though it might well have been recorded before then (for example in letters that have not survived). In fact the relevant passages must have been written before news of the death of Simon de Montfort in 1218 had reached Germany, since Caesarius says that Simon de Montfort is besieging toulouse "even to this day". Here are the relevant passages:

|

||||||

| It would be unusual, perhaps unique, for a Churchman to command a massacre of a whole town. |

It is not unusual, let alone unique, to find examples of Churchmen commanding massacres like this - and citing the Pope as the source of the command. We have several other examples from the Cathar Wars - for example another papal legate, Cardinal Bertrand, sent by Pope Honorius III in early 1217 was insistent that everyone in Toulouse should be put to death, saying "take care that no one escapes" (Laisse 186). When a bishop questions this, saying that all in church within sight of the alter should be saved, the Cardininal says "No" and insists that sentence has been passed. Later, Cardinal Bertrand exhorts the Crusaders and is very clear that "every one" of those living in the city should be massacred including implicilty, Catholics, children and babies and, explicitly women and the sick and injured. He points out that this is in line with his papal instructions:

As at Beziers, the churches would afford no protection. As it happened, the crusaders failed to take the city, so this particular threat of massacre was not realised. Massacres of God's enemies were seen as not merely necessary but somehow "merciful" and entirely in line with God's will. In November 1225 over a thousand senior churchmen attended a Church Council at Bourges. It was attended by 112 archbishops and bishops, more than 500 abbots, many deans and archdeacons, and over 100 representatives of cathedral chapters. This was well after the massacre of Beziers, and every one of those in attendance would have been aware of the massacre, yet there was no hint by the Council that Crusaders should ensure that no such atrocity should occur again. As the French poet Philip Mousket sang afterwards "One and all, the clergy unanimously decided that, for God's sake and for mercy, the Albigensians should be destroyed. (cited by Kay, Richard. The Council of Bourges, 1225: A documentary History. Aldershot,Ashgate, 2002, p311). |

||||||

| There is only one record of this event. |

There is only one record of most events in Medieval history. We do not normally discount such records, unless there is good reason to do so (such as hostile witness, or impossibility). We have no such reason here. Just a few months after the massacre at Béziers, Simon de Montfort encountered two heretics at Castres. One of them would not renounce his faith, but the other one would. The Crusaders disagreed as to whether he should be burned alive, or should be allowed to live. Simon took the initiative and reasoned as follows: if the heretic was telling the truth then the flames would expiate his sins and he would go the heaven; if he was lying then the flames would send him to hell [Historia 112-3]. This is exactly the reasoning attributed to Arnaud just a short time before. Certainly, the scale of the killing is different but the principle is identical. Similar reasoning is not recorded elsewhere (which is why Arnaud's words have such a terrible resonance). Can it really be a coincidence? Or is it more likely that Simon was applying a lesson learned from his mentor, Arnaud, at Béziers a short time previously? |

||||||

|

The words are consistent with what did in fact happen at Béziers under Arnaud Amaury's command. Arnaud was in supreme command of the Crusader army at Béziers. According to the most sympathetic source (Historia Albigensis by Pierre Des Vaux-de-Cernay, a contemporary chronicler and another fellow Cistercian who had been in the crusader army) everyone in the town was massacred including new-born babies. It does not seem likely that the Supreme Commander of God's Holy Army could be unable to save a single child if he had wanted to. |

|||||||

|

The words are consistent with other contemporary records, including Arnaud's own letter to Pope Innocent III after the massacre at Béziers which portrays the massacre of part of divinely engineered event. He says that "Our men [nostri] spared no-one, irrespective of rank, sex, or age, and put to the sword almost 20,000 people. After this great slaughter the whole city was despoiled and burnt, as Divine vengeance raged miraculously ..." (Patrologia latinae cursus completus, series Latina, 221 vols., ed. J-P Migne (1844-64), Paris, Vol. 216:col 139) |

|||||||

|

Caesarius's Dialogus miraculorum was a best seller of the Middle Ages - perhaps second only to the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. Many thousands of people would have read his story about Arnaud, including many who knew about Beziers at first hand, and who knew Arnaud personally. (The text was designed as and used as a teaching and preaching aid, so was widely repeated in church). We have no hint that anyone was offended by this accusation. No-one objected to it, no-one denied it. Nor was the story withdrawn from later editions. Arnaud Amaury died in 1225, after Caesarius's book had become widely available, so Caesarius would have every expectation that Arnaud himself would see it. Arnaud Amaury had been Abbot of Cîteaux when Dialogus miraculorum was published, Cîteaux being the mother-house of all Cistercian foundations. (The Cistercian order takes its name from this mother house at Cîteaux). Caesarius was a also a Cistercian monk. Given the status and prestige of Arnaud (also a Papal Legate), it seems unlikely that Caesarius would have made a statement about his prestigious superior that was not (a) true and (b) considered complimentary. Caesarius's confidence that his assertion would not be contradicted by Arnaud, or by any of his powerful friends, or by surviving Crusaders, or by his Cistercian colleagues, or by the papacy was clearly justified, and speaks volumes about how the event was considered at the time (and continued to be considered up to the nineteenth century). |

|||||||

| The Catholic Encyclopedia (under "Albigenses" states that these words were never spoken by Arnaud Amaury: 'The monstrous words: "Slay all; God will know His own," alleged to have been uttered at the capture of Béziers, by the papal legate, were never pronounced (Tamizey de Larroque, "Rev. des quest. hist." 1866, I, 168-91).' |

No-one ever seems to have thought to deny that the words were spoken until the nineteenth century when the Catholic Church first started to recognise a need to justify its historical record. Tamizey de Larroque offers no substantive reason to doubt that the words were pronounced, and the Catholic Encyclopedia offers no reason why we should believe a man who lived over half a millennium after the event and earned his living as a Catholic apologist, rather than a sympathetic well-informed, contemporary chronicler holding a senior position (master of novices) in a Cistercian monastery. (Cistercians having taken a leading role in the Crusade against the Cathars). Philippe Tamizey de Larroque, "Un épisode de la guerre des Albigeois", Revue des questions historiques, t. 1, 1866, p. 168-191 lists a number of reasons for doubting the words as reported.

Tamizey de Larroque does all he can to make his case. He places Simon de Montfort at the head of the Crusaders in place of Arnaud (who was in military command at the siege of Beziers). The southerners are presented as "rebels". The lands of the King of Aragon become "our provinces" (nos provinces). He says the words attributted to Arnaud are too barbaric to have been spoken by him - either unaware, or unwilling to disclose, that the words are modelled on a biblical passage. Caesarius, the "pious and learned monk" and "gifted and diligent scholar" who studied theology, philosophy and classics acknowledged by the Catholic Encycolopedia, whose "fame as teacher soon spread far beyond the walls of his monastery", is absent from Tamizey de Larroque's narrative. Instead Tamizey de Larroque repeatedly makes the point that Caeasarius was not just "foreign" but "German". He supposedly spends his life closetted in his cell, which seems unlikely for a Master of Novices who is known to have travelled widely. Caesarius (who is no less trustworthy than any other Church chronicler, and more highly esteemed than most) is dismissed as a credulous fool:

Tamizey de Larroque mentions the fact that the Bishop of Beziers warned of exacly such a massacre before the siege of Beziers, but misreprents it as a heart-felt warning to the inhabitants as though that mitigated the threat from Arnaud's Crusader army. In fact the contemporary account (from the Song of the Crusade) has Arnaud swearing to massacre men, children and infants. Tamizey de Larroqu dismisses this critical piece of evidence as an "exaggeration". Tamizey de Larroque does not consider any of the other points made on this page, for example that such a massacre was planned at Arnaud's Council of War just before the massacre, or that the Crusaders explicitly relied on total massacres as a deliberate terror tactic, or that no-one ever disputed the story until he did himself, some six and a half centuries later. He does not mention that thousands of Crusaders were also "German" and likely to have beein contact with Caesarius, nor that some of them would also have been Cistercians. He skates over the possibility that Caesarius might have known a number of first-hand witnesses - as many other Cistercians certainly did - going so far as to assume it an impossibility. Here is Tamizey de Larroque's summing up:

[my translation:]

Tamizey de Larroque introduces no other argument that is not addressed on this page, avoids mention of all counter arguments, and relies heavily on the fact that Caesarius of Heisterbach was remote from the event in space and time, and on the immorality of the injunction. He does not mention that other primary sources about the Cathar Crusades were also remote in time and distance from Beziers in 1209, not that other Church Chroniclers of the Crusade also relate stories of demons and miracles, and yet are considered reliable. He avoids mention of Gratian's Decretum and of the many other sources that confirm the Church's predeliction for massacre in the thirteenth century.

Click on the following link to read the full text of Tamizey de Larroque's article (in French): page 168, page 169, page 170, page 171, page 172, page 173, page 174, page 175, page 176, page 177, page 178, page 179, page 180, page 181, page 182, page 183, page 184, page 185, page 186, page 187, page 188, page 189, page 190, page 191 Or here (ocr version, so a bit flaky, especially the footnotes)

|

Cathar Beliefs and Waldensian Beliefs

Waldensians or Waldenses were followers of Peter Waldo. They originated in the late 12th century around 1176 as the Poor Men of Lyons, a group organized by Waldo, a wealthy merchant of Lyon. Waldo was a model Christian who gave away all of his property and went about preaching apostolic poverty as the way to salvation.

Waldo and his followers were Catholics, perfectly orthodox in every respect. But problems arose over the question of preaching. At the time, preaching required official Church permission, which Waldo was unable to secure from the Bishop in Lyon. In 1179 Waldo attended Pope Alexander III at the Third Lateran Council and asked for permission to preach. Walter Map, in De Nugis Curialium, narrates the discussions at one of these meetings. The pope, while praising Peter Waldo's ideal of poverty, ordered him not to preach unless he had the permission of the local clergy. He continued to preach without permission and by the early 1180s he and his followers were excommunicated and forced from Lyon.

The Catholic Church declared them heretics - the group's principle error was "contempt for ecclesiastical power" - that they dared to teach and preach outside of the control of the clergy "without divine inspiration". They were also accused of the ignorant teaching of "innumerable errors" and condemned for translating literally parts of the Bible which were deemed heretical by the Church. Waldo's teaching was very similar to that of Francis of Assisi, and his followers experienced a similar fate. St Francis's closest adherents, the Spiritual Franciscans, like Waldensians would be declared heretic and persecuted.

In attempting to justify their right to preach Waldensians read the bible closely and deduced that the papacy was mistaken not only in claiming the right to restrict their preaching, but also in a number of other respects - for example the role of priests as mediators between God and humankind, noting Matthew 23: "All of you are brethren." They also questioned the justification and extent of papal authority, and the interpretation of a number of biblical passages.

Waldensians were declared schismatics by Pope Lucius III in 1184 and heretics in 1215 by the Fourth Lateran Council, which anathemamitised them. The rejection by the Church radicalised the movement; the Waldensians became anti-Catholic - rejecting the authority of the clergy, declaring any oath to be a sin, claiming anyone could preach and that the Bible alone was all that was needed for salvation, and rejecting the concept of purgatory along with the adoration of relics and icons.

In 1211 more than 80 were burned as heretics at Strasbourg. So began centuries of severe persecution.

They were in many respects early Protestants. Waldenses proclaimed the Bible as the sole rule of life and faith. They rejected the papal authority and indulgences along with theological novelties of the time such as purgatory and the doctrine of transubstantiation. They laid stress on gospel simplicity. The doctrines included absolute poverty and non-violence. As they diverged from Catholic orthodoxy they started refusing the sacraments and denying the efficacy of the cult of Saints. They translated the bible into Occitan and established their own clergy. Services consisted of readings from the Bible, the Lord's Prayer, and sermons, which they believed could be preached by all Christians as depositories of the Holy Spirit.