Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the LanguedocCathar Beliefs |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Cathar Beliefs

Cathars clearly regarded themselves as good Christians, since that is exactly what they called themselves. On the surface, their basic beliefs seem unremarkable. Most people would have difficulty in distinguishing the principle Cathar beliefs from what are now regarded as conventional orthodox Christian beliefs. However, pursuing their fundamental beliefs to their logical conclusion revealed surprising implications (for example that Roman Catholics were mistakenly following a Satanic god rather than the beneficent god worshipped by the Cathars.) Like the earliest Christians, Cathars recognised no priesthood. They did however distinguish between ordinary believers (Credentes) and a smaller, inner circle of leaders initiated in secret knowledge, known at the time as boni homines, Bonneshommes or "Goodmen" , now generally referred to as the Elect or as Parfaits. Cathars had a Church hierarchy and a number of rites and ceremonies. They believed in reincarnation, and in heaven, but not in hell as it is now normally conceived by mainstream Christians. The Cathar view was that their theology was older than that of the Roman Church and that the Roman Church had corrupted its own scripture, invented new doctrine and abandoned the beliefs and practices of the Early Church. The Catholic view, of course was exactly the opposite, they imagined Catharism to be a badly distorted version of Catholicism. In addition to accusing the Cathars of faulty theology, they imagined a range abominable practices which would have been amusing except that, converted into propaganda, they led to the death of countless thousands through the Cathar Crusades and the Inquisition. The Roman Church seemed to have successfully extirpated Cathars and Cathar beliefs by the early fourteenth century, but the truth is more complicated. For one thing, modern historians have shown that many Catholic claims were false, while they have vindicated many Cathar claims; and there is a case that the Cathar legacy is more influential today than has been at any time over the last seven hundred years. Cathars were Dualists. That is, they believed in two universal principles, a good God and a bad God, much like the Jehovah and Satan of mainstream Christianity. As Dualists, they belonged to a tradition that was already ancient in the days of Jesus. (The revered Magi in the nativity story were Zoroastrians - Persian Dualists). Dualism came, and still comes, in many flavours. Even the Cathar variety came in more than one flavour, but the principal one was this: The Good God was the god of all immaterial things (such as light and souls). The bad God was the god of all material things, including the world and everything in it. He had contrived to capture souls and imprison them in human bodies through the process of conception. As Cathars put it, we are all divine sparks, even angels, imprisoned in tunics of flesh. According to later Cathar ideas, when we die the powers of the air throng around and persecute the newly released soul, which flees into the first lodging of clay that it finds. This "lodging of clay" might be human or animal. The soul would therefore be condemned to a cycle of rebirth, trapped in another physical body. By leading a good enough life human beings or rather their souls could win freedom from imprisonment and return to heaven, the immaterial realm of the good god. For members of the Elect, those who had undertaken the Consolamentum, death was no more than taking off a dirty tunic. The realm of the Good God, heaven, was filled with light. Some Cathars regarded the stars as divine sparks, or souls, or angels, in heaven. The realm of the bad god was the material world in which we serve out our earthly terms. Satan had entrapped these divine sparks and created humankind as their prison. Thus there was a part of the Good God trapped in all men and women, longing to rejoin its Maker. The Bad God filled humankind with temptations to frustrate souls from ever making that reunion. They could be tortured by disease, famine and other travails, including man's own inhumanity to his fellow man. Yet the Bad God had no power over the soul - a divine spark of the Good God. His remit was confined to material things. Any hell that existed was here on this material earth. To confound the Bad God it was necessary to abstain from all earthly temptations and to strengthen the inner spirit by prayer. It was an argument that seemed to provide a rational explanation for all the misfortunes of the world. Dualist ideas had a long history, stretching back well into pre-Christian times. All of the essentials were known to the Greek philosophers. Plato held that the soul yearns to fly home on the wings of love to the world of ideas. According to him it longs to be freed from the chains of the body. Early Christianity had adopted Neoplatonist ideas. Neoplatonism taught a doctrine of salvation alongside Dualism. Human bodies were material objects made of earth and dust, but our immortal souls were not, they were sparks of the divine. The divine was characterised as light, opposed to the darkness. According to Plotinus, souls were illuminated by the divine light. Matter on the other hand was just darkness, and had no real existence. These Neoplatonist ideas were an integral part of Early Christianity, later dropped in mainstream Christianity when it switched from Plato's philosophy to Aristotle's as a result of Thomas Aquinas's attempts to reconcile Christianity with Aristotle's philosophy. The Cathars' teachings on this, as on many other matters, reiterate those of the early Church. They provide one of a number of pieces of circumstantial evidence that their origins date from early Christian times. The idea that flesh was inherently evil became popular in mainstream Christianity too - it was formalised in the concept of Original Sin and was enormously popular up until the twentieth century. Significantly, the doctrine of Original Sin was invented by St Augustine, a Christian who had previously been a Manicaean - ie a Gnostic Dualist. Today this traditional teaching is played down, and it comes as a shock to many Christians to hear the words like that of the Burial service from the Book of Common Prayer, contrasting an evil material body with a good spiritual one: ".... our Lord Jesus Christ, who shall change our vile body that it may be like to his glorious body." Cathars were also Gnostics. Gnostics believed, and still believe, that divine knowledge is granted only to an inner elite, like the "esoteric" knowledge of the Pythagoreans. The inner elite undertook a long period of training before becoming being formally accepted as members of the elite, and thereafter leading severely ascetic lives. Their lives of meditation, fasting, hardship, poverty and good works matched exactly the highest ideals of Catholic and Orthodox hermits, monks and friars. The Cathar Elect are now popularly known Parfaits or "Perfects", though they never referred to themselves as such. They also believed in metempsychosis or the transmigration of souls, as had the Pythagoreans. In other words, both Pythagoreans and Cathars believed not only in reincarnation but in the rebirth of the soul in animals as well as humans - and both refrained from eating meat for exactly this reason. Cathars were also universalists, which means that they believed in the ultimate salvation of all human beings. Here is an account of how they saw themselves, recorded in 1143 or 1144 by Eberwin, Prior of the Premonstratensian Abbey of Steinfeld writing to Bernard of Clairvaux (St Bernard):

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Basic Tenets

Cathars were Gnostic Dualist Christians who claimed to retain many of the beliefs and practices of the early Christian Church. All of their beliefs stemmed from logical deductions from a combination of these three fundamental beliefs (Gnosticism, Dualism and Christianity) For example they displayed contempt for everything material, a position with enormous ramifications, based on their Dualism. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dualism

The Cathars were Dualists. That is, they believed in two universal principles, a good God and a bad God, much like the Javeh and Satan of mainstream Christianity. As Dualists, they belonged to a tradition that was already ancient in the days of Jesus. (The revered Magi in the nativity story were Zoroastrians - Persian Dualists. Dualism came, and still comes, in many flavours. Even the Cathar variety came in more than one flavour, but the principal one was this: The Good God was the god of all immaterial things (such as light and souls). The bad God was the god of all material things, including the world and everything in it. He had contrived to capture souls and imprison them in human bodies through the process of conception. As Cathars put it, we are all divine sparks, even angels, imprisoned in a tunic of flesh. According to later Cathar ideas, when we die the powers of the air throng around and persecute the newly released soul, which flees into the first lodging of clay that it finds. This "lodging of clay" might be human or animal. The soul would therefore be condemned to cycle of rebirth, trapped in another physical body. By leading a good enough life human beings or rather their souls could win freedom from imprisonment and return to heaven, the immaterial realm of the good god. For members of the Cathar Elect, death was no more than taking off a dirty tunic. The realm of the Good God, heaven, was filled with light. (Some Cathars regarded the stars as divine sparks, or souls, or angels, in heaven). The realm of the bad god was the material world in which we serve out our earthly terms. Satan had entrapped these divine sparks and created humankind as their prison. Thus there was a part of the Good God trapped in all men and women, longing to rejoin its Maker. The Bad God filled humankind with temptations to frustrate souls from ever making that reunion. They could be tortured by disease, famine and other travails, including man's own inhumanity to his fellow man. Yet the Bad God had no power over the soul - a divine spark of the Good God. His remit was confined to material things. Any hell that existed was here on this material earth. To confound the Bad God it was necessary to abstain from all earthly temptations and to strengthen the inner spirit by prayer. It was a persuasive argument and it seemed to provide a rational explanation for all the misfortunes of the world. Early Christianity adopted Neoplatonist ideas and these ideas paralleled Dualist ideas. Neoplatonism taught a doctrine of salvation alongside Dualism. Human bodies were material objects made of earth and dust, but our immortal souls were not, they were sparks of the divine. The divine was characterised as light, opposed to the darkness. According to Plotinus, souls were illuminated by the divine light. Matter on the other hand was just darkness, and had no real existence. These Neoplatonist ideas were an integral part of Early Christianity, later dropped in mainstream Christianity when it switched from Plato's philosophy to Aristotle's as a result of Thomas Aquinas's attempts to reconcile Christianity with Aristotle's philosophy. The Cathars' teachings on this, as on many other matters, reiterate those of the early Church, and suggest that their origins date from early Christian times. The Cathar Consolamentum, almost certainly preserves this ancient tradition:

Many early Christian writings reflect the same early Christian distaste and even loathing of the material world. Most of these writings were discarded from the orthodox version of the New Testament, but a few passages made it into canonical scripture. Here for example is 1 John 2:15-17

The idea that flesh was inherently evil was particularly popular in mainstream Christianity - it was formalised in the concept of Original Sin and was enormously popular up until the twentieth century. Today this traditional teaching is played down, and it comes as a shock to many Christians to hear the words like that of the Burial service from the Book of Common Prayer, contrasting an evil material body with a good spiritual one: ".... our Lord Jesus Christ, who shall change our vile body that it may be like to his glorious body." |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GnosticismCathars were also Gnostics. Gnostics believed, and still believe, that divine knowledge is granted only to an inner elite, like the "esoteric" knowledge of the Pythagoreans. The inner elite undertook a long period of training before leading severely ascetic lives. These were the Cathar Elect, or as they are now popularly known Parfaits. Cathars were also universalists, which means that they believed in the ultimate salvation of all human beings. Here is an account of how they saw themselves, recorded in 1143 or 1144 by Eberwin, Prior of the Premonstratensian Abbey of Steinfeld writing to Bernard of Clairvaux (St Bernard):

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Implications of Cathar Beliefs

The idea that human beings were sparks of light trapped in tunics of material flesh had a number of logical consequences:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cathar Church Hierarchy

Cathars did not regard Parfaits as priests. Parfaits did exercise sacramental responsibilities but did not carry out sacrifices, the defining activity of a priest. The New Testament word often translated as priest, presbyter, does not really mean "priest". It means "elder", which is how it is translated in many modern bibles. Perhaps significantly, the New Testament never uses the word priest (sacerdos) nor does it talk about a priesthood (except in the sense that all believers are priests). In this, as in much else, historians concur that Cathars appear to represent a survival of the Earliest Christian Church. Although the Cathars did not recognise a priesthood, they did elect bishops from among the elect. These were bishops in the sense that the word (episcopos) is used in the New Testament - it could reasonably be translated into English as supervisor. Cathar bishops were responsible for distinct areas. Various

bishoprics were mentioned including Toulouse,

Carcassonne,

Albi, Agen, Lombers, Saint-Paul, Cabaret,

Servian and Montségur

( When a bishop died another official, the Elder Son (filius major), would take his place. The Younger Son (filius minor) would replace the Elder Son and a new Younger Son would be chosen from the existing Elect. The Elder and Younger sons can conveniently be regarded as first and second deacons respectively. Cathar Deacons were tasked with the Apareilementum (or public confession). Some authorities, including Jean Duvernoy, claim that each Deacon controlled a region. Among the seats of the deacons were Moissac, Cordes, Toulouse, Puylaurens, Avignonet, Fanjeaux, Montr�al, Carcassonne, Mirepoix, Le Bézu , Puilaurens, Peyrepertuse, Qu�ribus, and Tarascon-sur-Ari�ge. Historians disagree about the existence of Deaconesses. Cathars did not recognise the hierarchy of the Roman Church, much of which has no biblical sanction. There are for example no archbishops, metropolitans, primates, cardinals, patriarchs, or popes mentioned in the New Testament. For a long time the Catholics accused the Cathars of having their own Pope, apparently misunderstanding the famous visit of Cathar bishop from the Balkans to a Cathar Council in the Languedoc. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ordinary Believers

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cathars in England Cathars spread throughout Europe and are recorded in many countries. A group of some 30 men and women, referred to as Publicans, were detected in England. They were brought before a synod of bishops and King Henry II at Oxford probably in the winter of 1165.

The quotation is from William of Newburgh's history of the Kings of England, written around 1199-1201: Willelmi Parvi, canonici de Novoburgo, historia rerum anglicarum 1. xiii ed. by Richard Howlett, in Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I (Rolls Series, LXXXII [4 vols, London, 1884-1889] I 131-34). English translation from Wakefield and Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, 40 (pp 245 - 247). ( Here's another, fuller translation:

The Church Historians of England, Vol IV, Part II, The History of William of Newburgh: The Chronicles of Robert de Monte, Rev Joseph Stevenson, (London: Seeleys, 1856), Chapter XIII, (pp. 460-1). (availble on Google Books)

We can only speculate at how gratified the bishops must have been that not a single member of their Christian flock offered not "the slightest pity" to their mutilated, stripped, resoundingly scourged, Christian brethren from overseas, but instead left them to starve or freeze to death in the bitter winter cold. |

The Elect (Parfaits and Parfaites)

When a believer underwent the Consolamentum, his or her life changed for ever. After this rite they were members of the Elect. From now on they would lead the life of an ascetic. They were to be completely chaste, and were not permitted even to touch members of the opposite sex. They were not permitted to tell a lie, swear an oath, nor kill any living creature. They would have to undertake frequent fasts, including three 40 day fasts each year.

For those who expected to die within hours this had less significance than for those who undertook the rite without the expectation of imminent death. They lived simple, peaceful, devotional, chaste lives of poverty, often travelling on foot in pairs like the disciples, preaching and working in simple trades like weaving to earn their living. To their followers the Elect were living saints. Touched by the Holy Spirit, they were God's ambassadors in an alien world. The contrast with bejewelled, warmongering, sybaritic, indolent, lascivious Churchmen living on forcibly extorted tithes was difficult for the slowest peasant to miss.

The Elect were not an ordained priesthood, though their Catholic critics never seem to have fully understood this (and even modern works still refer to Parfaits as "priests"). The defining feature of a priest is that he makes sacrifices to a divinity - something that Parfaits did not do, and so cannot correctly be called priests. They did however minister and preach, and they also controlled the Church, electing their own bishops. They received from the Believers unquestioning obedience. As vessels in whom the Holy Spirit dwelt, they were adored by the faithful, who would prostrate themselves before them whenever they asked for their prayers. (Another practice dating from the earliest days of Christianity). The Elect alone were adopted sons of God. Ordinary believers would ask members of the Elect to pray to the Good God for them - specifically for the Good God to lead them to a good death.

The Elect were not permitted to eat meat, or other animal products such as cheese, eggs or milk. All of these were held to be produced per Siam generatinis sen coitus, and everything sexually begotten was impure. Another reason why the Perfect should not eat animals was that a human soul might be imprisoned in its body. Curiously, the Elect were permitted to eat fish. Fish were believed to be born in the water without sexual connection, and on the foundation of this fallacy Christians framed their fasting rules. As they pointed out, the Jesus of Gospels was recorded as having eaten fish but not meat. (The common practice of eating fish but not meat on Fridays is a Catholic vestige of the same Mediaeval fallacy.) Vegetarianism was regarded as evidence of heresy, as was the refusal to kill any animal, as Cathars interpreted the commandment "Thou shalt not kill" as referring to all animals (The original Hebrew is ambiguous and some Jewish scholars have agreed with the Cathar reading, some with the Catholic reading).

As well as refusal to kill, Inquisitors had a range of easy ways of identifying Cathar Parfaits. Before the real persecutions started they had always worn black robes, but they stopped doing that when the persecutions began in earnest. They also refused to swear oaths in any circumstances, which made it easy to identify them once subject to questioning. To identify them in the first place a good indicator was their pale countenance. With rigorous fasting throughout the year, their pallor often gave them away. Too bad for anyone who just happened to have a light complexion. The Faithful, unless they were checked, would kill anyone that did not look like a healthy meat eater. As on other occasions the unusually liberal Bishop Wazo of Liege had trouble enforcing rationality among the faithful:

... in a measure he [Wazo] curbed the habitual headstrong madness of the French, who yearned to shed blood. For he had heard that they identified heretics by pallor alone, as if it were certain fact that those who have a pale complexion are heretics. Thus, through error coupled with cruelty, many truly Catholic persons had been killed in the past.

(Extract from Gesta episcoporum Leodiensium from the period 1043-1048, translated from Latin into English; Cited by Walter Wakefield & Austin Evans, Heresies of The High Middle Ages (Columbia, 1991) p 93)

Even the liberal Bishop Wazo had qualms only about the killing of Catholics - not about killing Cathars.

From all the evidence we have, the Cathars of the Languedoc were highly respected by those who knew them best. The contrast with local Catholic churchmen was apparent to all. The medieval historian Sir Steven Runciman having indicated the shortcomings of senior churchmen, goes on:

The parish priests, faced with such examples, either followed suit or sank into despondent apathy. Some, like the chaplain of Saint-Michel de Lanes, who would not interrupt his gaming even to celebrate the Sacraments, were as worldly as any of their superiors. Others were frankly immoral, like the chaplain of Rieux-en-Val, who lived with the lady of the village, after she had murdered her husband. Others again, to save trouble, maintained the friendliest relations with the heretics and even were present at their ceremonies. None of them could command a fraction of the respect given to the heretic leaders either for the purity of their lives or for the force and efficacy of their preaching.

Steven Runciman, The Medieval Manichee (Cambridge University Press, 1999) p 136 (for those who are interested, Sir Steven provides references for each of the last 5 sentences of this paragraph)

|

|

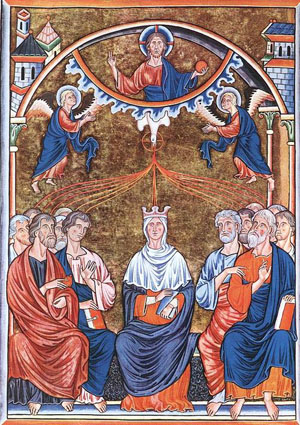

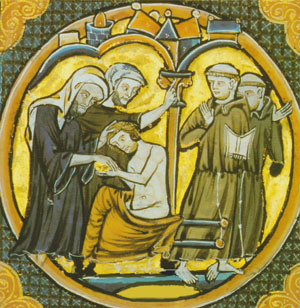

MINIATURIST, French, Ingeborg Psalter, c. 1195, Manuscript (Ms. 9), 304 x 204 mm, Musée Condé, Chantilly |

|

|

Pentecost, 1386 Armenia |

|

Cathar Ceremonies

The central Cathar rite was the Consolamentum, or Baptism of the Holy Spirit and fire referred to in the New Testament. The Holy Spirit derived from God and was sent by Christ. The Consolamentum removed all sin, reversed the effects of the Fall, and restored the lost tunic of immortality. A Consoled person is an angel walking in the flesh, separated from heaven by a thin veil of death. Only a Parfait could administer the Consolamentum. It was striking in its simplicity, and seems to have faithfully preserved a ceremony of the very earliest Christian Church.

Cathars had a ceremony corresponding to the Catholic mass or Eucharist, but again bearing a striking resemblance the ceremony of the Early Church. They blessed bread and shared it between them, though none imagined that its substance was anything other than bread. (It is odd that even bread could have held any virtue since as a material object it belonged to the realm of the Evil god, and for this reason some Cathars seem to have rejected the idea of blessed bread). At the other end of the spectrum, some Cathars would reserve part of their blessed bread and keep it, perhaps for years, eating of it occasionally though only after saying the Benedicite (As the Church Father Tertullian relates of his contemporaries in the 2nd century).

|

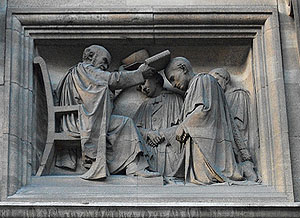

The ordination of modern Christian priests involves the laying on of hands, a vestige of early Christian baptism, as retained by medieval Cathars. |

|

|

Papal Ordination (Acts 6.6) |

|

|

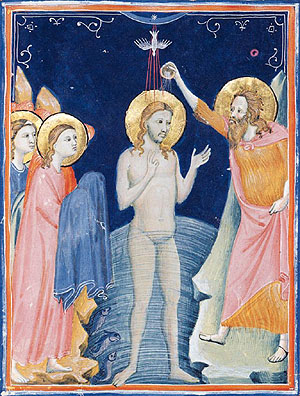

Christ being baptised by John the Baptist

in the River Jordan. (note the holy spirit in the form of

a white dove) |

|

Consolamentum or Consolament.

The Consolamentum was a spiritual baptism, as described in the New Testament, where the Jewish practice of baptism by water was abrogated, and baptism by fire implemented. (Modern Christians remember this as Pentecost and some, Pentecostalists, make it the main feature of their theology). Only a Parfait could administer the Consolamentum, which meant that every new Parfait stood at the end of a chain of predecessor Parfaits linking him or her to the apostles and to Jesus himself.

It was the most significant ceremony in Cathar theology, marking the transition from ordinary believer (auditore or credente) to to Parfait, one of the elect. During the ceremony the Holy Spirit was believed to descend from heaven, and part of the Holy Spirit would then inhabit the Parfait's corporal body. It was largely because of this indwelling portion of the Holy Spirit that Parfaits were expected and willing to lead such austere ascetic lives, and why ordinary believers were prepared to "adore" them.

The ceremony was striking in its simplicity. It required no material elements such as water or anointing oil, and seems to have preserved a ceremony of the very earliest Christian Church. For Cathars this was hardly surprising, since they claimed that the the rite had been appointed by Christ, and had been handed down from generation to generation by the boni homines. For Catholics it was rather a mystery and their best explanation was that the Cathar rite was a distorted imitation of various Catholic rites.

The Consolamentum was also given to sick or injured believers, in the expectation of death. As long as they died quickly this presented no great problem as they had little opportunity to fall back into sin. But if they recovered they were now Parfaits, and presumably expected to behave as such. Some authorities (notably Jean Duvernoy) differentiate between the baptism of the Perfects, from the 'Solace' baptism granted to the dying for the remission of their sins. Even though both rites are identical those who received the 'Solace' baptism and survived seem to have been obliged to then undertake the normal training and receive the Consolamentum again to became a fully functioning member of the Elect.

Becoming a Parfait or Parfaite required a long period of probation and instruction, just as becoming a Christian did in the early Church. Compare the following statements accurately reflecting three different views of how to become a member of the Church of Christ:

|

Medieval Catholic

|

Early Church

|

Cathar Church

|

| A person would be received into the Church by being baptised, without necessarily needing to give their consent, as in the case of infant baptism. |

A person would be received into the Church in one of two circumstances. They would be deemed worthy after a long period of preparation and instruction or they would request to be received on their deathbed. In either case they would need to give their consent. |

A person would be received into the Church in one of two circumstances. They would be deemed worthy after a long period of preparation and instruction or they would request to be received on their deathbed. In either case they would need to give their consent. |

As Wakefield and Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, § 57 (p 465), put it "Like a catechumen of the early Church - Catharist practices reflect the ancient usage - a believer had to undergo a period of probation, normally at least a year, during which he was instructed in the faith and disciplined in a life of rigorous asceticism"

|

Wakefield and Evans cite Jean Guiraud, "Le consolamentum cathare", Revue Des questions historiques, new series XXXI (1904), 74-112, and refer also to Dondaine, Un Traiténéo-manichéen du XIIIe siècle: Le Liber de duobus principus, suivi d'un fragment de rituel cathare (Rome, 1939), pp 45-46, and Arno Borst, Die Katharer (Schriften der Monumenta Germaniae Historica, XII (Stuttgart, 1953) PP 193-96. |

Click on the following link for the detailed account of the ceremony

of the Consolamentum

(taken from the Traditio - the Lyons Ritual) in Occitan and English

Below is a summary of what it involved.

After a long period of training and fasting, the rite proceeded as follows:- The "Melhoramentum"

- The Perfect held the Bible above the kneeling postulant's head and recited the "Benedicite" .

- The postulant received from a Parfait a copy of the "The Pater" (Lord's Prayer).

- The Perfect addressed the postulant and explained to him from Scripture the indwelling of the spirit in the Perfect, and his adoption as a son by God.

- The Lord's Prayer was then repeated by the postulant, the Perfect explaining it clause by clause.

- There followed the Renunciation, primitive in form, except that it (in some cases it was adapted so that the postulant solemnly renounced the harlot church of the persecutors and their replicas of the cross, their sham baptisms and their other magical rites).

- Next followed the spiritual baptism itself, consisting of the imposition of hands, and the touching of the Gospel on the postulant's head.

- The Parfait's vocation was then defined, he or she was reminded of all the things that are forbidden, and of what was required of them: pardoning wrongdoers, loving enemies, praying for those who calumniate and accuse, offering the other cheek to the smiter, giving up one's mantle to him that takes one's tunic, neither judging nor condemning. Asked if he will fulfil each of these requirements, the postulant answered: "I have this will and determination. Pray God for me that he give me his strength".

- The next part of the rite reproduced the confiteor as it existed in the 2nd century, asking pardon for previous sins.

- Then followed the act of consoling. The Perfect took the Gospel and placed it on the postulant's head. Other Perfects present placed their right hands on the postulant's head.

- They then three times adored the Father and Son and Holy Spirit and said a prayer asking God to welcome his servant and to send down the Holy Spirit.

- They then said the parcias, and repeated three times the "Let us adore the Father and Son and Holy Spirit", and then pray: "Holy Father, welcome thy servant in thy justice and send upon him thy grace and thy holy spirit."

- Then they repeated the adoration and the The Lord's Prayer, then read the John Gospel (1:1-17). This was the most solemn part of the rite, for the postulant was now a Perfect.

- All Perfects present would give the kiss of peace and the rite was over.

.The Cathars did have other ceremonies, or quasi-ceremonies, including the following.

|

Franciscan Friars witness a Cathar Consolamentum (Bible illumination, Bibliothèque nationale de France) |

|

|

A modern reproduction of the ceremony of the Consolamentum |

|

|

The Cathars, like Saint Cuthbert, especially favoured the Gospel of Saint John. |

|

|

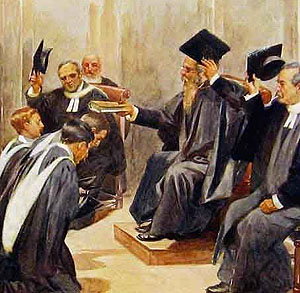

Doctoral degrees were conferred at Oxford University by the Vice Chancellor in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, while tapping the new Doctor on the head with a New Testament - remnant of the Medieval ceremony when the award was a sort of Christian admission ceremony - sharing a common origin with Cathar practices. (Photo of the Examination Schools, Oxford) |

|

|

Doctoral degrees are still conferred at Oxford University by the Vice Chancellor in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, while tapping the new Doctor on the head with a New Testament - it is now optional. (Conferring Degrees in the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford. Page From The King's Empire C1910) |

|

Melhoramentum.

Not really much of a ceremony, more a formal greeting. Derived from an Occitan word meaning improving, the Melhoramentum was the acknowledgement by a believer of the Holy Spirit dwelling with the Parfait.

The believer would kneel and, with both hands folded, bow three times to the ground. On each genuflexion the believer would say: �Bless me, Lord; pray for me�. Then, the Cathar prayed : �Lead us to our rightful end�. The perfect, man or woman, then answered �God bless you... In our prayers, we ask from God to make a good Christian out of you and lead you to your rightful end�.

As so often, the Catholics never really seem to have understood what this was about. This practice was often regarded as worship or as they usually put it "adoration" of the Parfait.

Click on the following link for the Melhormentum

(taken from the Traditio - the Lyons Ritual) in Occitan and English

Lo Servissi (The "Service")

the Apareilementum or Aparelhament.

This was a monthly rite involving a public and a solemn confession, identical to the earliest form of confession known in the Christian Church.

The aparelhament could give rise to punishments, ranging from prayers with genuflection to fasting. Absolution was given en "masse".

The rite was restricted to the Elect and formed part of the ceremony

of Cathar Baptism or Consolamentum. Click on the following link

for the Servissi

(taken from the Traditio - the Lyons Ritual) in Occitan and English

Convenenza.

The opportunity to undergo the Consolamentum on one's deathbed presupposed that death would not come quickly. (The problem is similar to that of modern Catholics who believe in the efficacy of the Last Rights or Extreme Unction). In time of War, the problem was more acute as men were often left conscious, but dying and deprived of speech. The solution was a ceremony called Convenenza. It was not itself a Consolamentum, but it fulfilled the parts of the Consolamentum that required the candidate to respond and make undertakings. The Consolamentum could then be administered subsequently if the candidate was wounded and could not speak.

The Convenenza seems to have been common before battles and during sieges. We have a first hand account of this practice, taken from the D�position de Guillaume Tardieu de la Galiole (translated by Jean Duvernoy �Le Dossier de Monts�gur : interrogatoires d'lnquisition 1242-1247�):

�... Then, on this Perfect's request, I devoted myself to God and the Gospel and promised to no longer eat meat, eggs, cheese and fat apart from oil and fish. I also promised not to swear in all my life, and to forsake the sect out of fear of fire, water and other kinds of death. After this oath, I recited the Pater Noster in the Parfaits' manner, then the Perfait held the book above my head and read the Gospel of Saint John. After this, they gave me peace first with the book and then with the mouth, kissing me twice across the mouth and prayed God, amidst much kneeling and "venias"�

Sir Seven Runciman, in The Medieval Manichee (CUP, 1982) PP 152-3) has a slightly different viewpoint, and seems to consider the Convenenza to be more generally available as a sort of preliminary membership.

Before the rite of entry into the sect, the ceremony of the Convenenza (Convenientia), could be performed, the would-be believer had to be adjudged a suitable recipient. Large numbers of persons who certainly sympathised with and even believed in the heresy never went through the ceremony. It was only when they were already besieged in Montségur in 1244 that the soldiers who were fighting for Catharism all celebrated the Convenenza. Till then they had not strictly been members of the sect.

At the ceremony of the Convenenza the celebrant made one promise. to honour the superior cast: in the sect, the Perfects, and to hold himself at their disposal whenever they should need him. In return he was promised that he should have the second initiatory rite, the Consolamentum, that would make him a Perfect, administered to him on his deathbed, or sooner if he so desired. In the latter case the initiation was very stringent. The noviciate might last for a year or more, and the candidate would be very carefully examined to be sure that he could stand the rigours of a Perfect's life. William Tardieu told the Inquisitor: that for a year he was kept as a novice under the charge of a Perfect; but because he fell very ill he was given the Consolamentum sooner than at first was intended, as his death seemed probable. Dulcia of Villeneuve-la—Comtal was kept as a novice for three years in various establishment: of Perfect women and then it was decided that she was still too young and her vocation was not clear enough. Raymonde Jougla of Saint-Martin de Lande, a. candidate who for a year Was being prepared at a community of Perfect women, was left behind by them when they fled for safety to Montségur, as they did not think her nearly ready—she was not firm enough in the faith. The period of preparation, the Abstinentia, lasted for a year at least; and during that time the candidate had to live a life of the utmost austerity and strictness, under the care of some Perfect.

Endura

This is not really a rite or ceremony, so much as a practice amounting

to voluntary euthanasia. The Occitan word  Endura translates as "fasting".

Endura translates as "fasting".

In certain circumstances, believers would take the Consolamentum and then starve themselves to death. This might be done for example during an extended terminal illness, or in expectation of falling into the hands of the Inquisitors. Why hang around in hell, when freedom is within easy reach to those who have undertaken the Consolamentum? The practice of suicide was after all common among early Christians. We have the testimony of a Roman magistrate addressing a group of early Christians who were asking him to execute them. He told them it was easy enough to buy some rope or find a suitable precipice.

Although the practice is entirely in line with Cathar theology, and is attested in contemporary documentary evidence, there is some doubt about how common it was. References to it are rare, late and often suspicious - bearing the hallmarks of hostile witnesses. The case of Guilhelma, a resident of Toulouse for example, is typical of suspicious reportage - she is supposed to have regularly bled herself while sitting in a hot bath, and eventually poisoned herself and ate ground glass.

Since Catholics regarded suicide as a great sin, they seem to have made the most of the Cathar acceptance of it. (In much the same way that they exploited a second charge that they found so horrifying and that was apparently true - that Cathars used and had no objection to contraception). Many Catholic works, even modern ones, make out that suicide was a routine and frequent practice, and it is not unknown for propagandists to claim, or more often hint, that many Cathars spent their lives in repeated suicide attempts - starving themselves, slashing their wrists, poisoning themselves and consuming powdered glass. These accusations are based on the one isolated and questionable story of Guilhelma - and rely on an old myth that eating powdered glass will cause death. In fact there is no evidence that suicide was more common among Cathars than it was, or still is, among Catholics. The only known difference was the level of acceptance in the two communities.

The idea of a "good end" is an old one. The term euthanasia comes from the Greek. Hippocrates used it. It translates in English literally as "good end". The Cathars on leaving each other would say not Goodbye ["God be with you"] but "May you come to a good end" - meaning "may you die having undertaken the consolamentum". This was the best possible death as it meant the release of the soul from its cycle of reincarnation. There are hints that the idea of wishing one's coreligionists a "good end" was more widespread, and might have been known to Persian Manichaeans or even Zoroastrians.

|

The picture below shows a Persian ceramic dish dating from 1470-1481, the Timurid period. It is underglaze-painted fritware. The interesting thing about it is that around the center rosette are words that translate as "may you come to a good end" - repeated three times. |

|

|

Location: the Walters Art Museum, 600 N. Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21201 (Centre Street: Third Floor: Islamic Art) [but is it Islamic or Zoroastrian?]. Accession number 48.1031. 3 1/8 x 14 9/16 in. (8 x 37 cm) |

|

Reincarnation and the Afterlife

Many religions teach that there is an afterlife for humans and sometimes for other animals too. The Greeks had a concept of an afterlife - though it was a rather ill-defined and shadowy one. For heroes there was the prospect of eternity in paradise, a Greek equivalent of Valhalla. For particularly evil people there was the prospect of eternal punishment in Tartarus. But for the most part, the dead would live an anaemic afterlife with no action and not even their earthly memories.

Some Greek sects taught reincarnation, or more precisely the transmigration of souls. According to the esoteric teachings of Pythagoras for example, after death the spirit of one creature might pass after death into the body of another one.

The Jews had originally had no concept of an afterlife, but under Greek influence they had developed an ill-defined belief in an afterlife by the time of Jesus Christ. (The words translated as hell in the Old Testament actually mean grave or rubbish-tip). According to the New Testament Jesus seems to have held that there was a fully developed afterlife in heaven or hell. Ideas such as Purgatory and Limbo were developed much later. More conservative Jews at the time of Jesus still held ideas of an afterlife to be an offensive novelty. As they pointed out the many punishments promised by God in scripture are all punishments in this world. None is promised for an afterlife.

|

Egyptians believed that the cycle of rebirth was available only to those who had lived properly before death. On its first encounter with Osiris they imagined that the soul had to undergo a judgement, in which the heart (the seat of thought and emotion) was balanced on a scale against a feather, the symbol of the goddess Ma'at (representing the correct order of things). If the two did not balance, the soul was denied the chance to enter the cycle of rebirth

|

|

|

The following text is an extract from a work by Julian Moore. It summarises the Egyptian beliefs concerning the Judgement as depicted above. Note how Christianity has adapted them, with St Michael in the Anubis role, and Satan in the role of Ammit. Gomeisa The ways of life are manifold,

the ways beyond uncountable, Whether thin and frayed

by chafing time it seems no longer equal Upon that day Anubis will

be standing there. He conducts the soul And yet the way of death

is also barred. He who would come forth by day So let his mouth be opened

up that he may speak. Let Ptah, Then once within he must

address in turn the sovereign judges Anubis of the jackal head

accepts his heart and places it upon the scales Then, having heard the

verdicts of the judges and the scales, Osiris shall decree A name may be remembered

in the House of Fire by those whose hearts are just. Anubis yet waits overhead; he waits for death, for death will come. And it is here Gomeisa shines. © Julian Moore, 2007 |

From the more liberal Jews in an Hellenic world, early Christians had ready-made concepts of life after death, fuelled perhaps by other popular religions - Resurrection cults, Egyptian cults, Zorostrianism and even Buddhism (Buddhist missionaries are known in the Middle East at this time). What we now regard as mainstream Christianity slowly evolved its ideas of an afterlife, selecting popular ideas from other religions.

For example, the popular medieval idea of St Michael weighing the soul of the newly dead to determine whether it should go to heaven or hell is a direct copy of an Egyptian idea. In depictions of the scene, Christians simply substituted Michael for the original Egyptian god. Early Christians do not seem to have a clear idea about the afterlife, and some of them clearly believed in reincarnation. Christian sects such as the Sethians and the followers of the Gnostic Church of Valentinus believed in reincarnation. A Church Council was required to settle the matter some centuries into the development of "orthodox" Christianity. (Fifth General Council, 553, in condemning Origen's doctrine of pre-existing souls)

The Gnostic strands of early Christianity were more attracted to ideas of reincarnation and transmigration of souls (metempsychosis). These strands ran from the early Gnostic Dualists, through Manichaeism, the Paulicians, the Bogomils, the Italian Patarenes and into western Europe, including the Cathars of the Languedoc.

The beliefs seem to have varied in some details from time to time and place to place, but the following represents a fair if slightly simplified version of their beliefs:

|

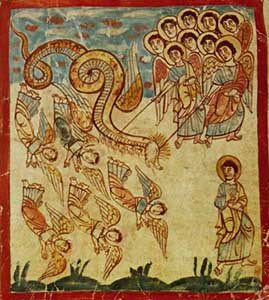

The Fall of the angels depicted in an Apocalypse

from Northern France, circa 800. The chief angel has changed

into a serpent during his fall and the lesser angels are losing

their haloes. Their wings are already shrinking too. |

|

|

Pythagoras |

|

Heaven

Heaven was the realm of the Good God, the god who had made all immaterial things including light and souls. These souls could be thought of as immaterial angels. They belonged in heaven, the realm of light, but some of them had somehow been captured by the Bad God and imprisoned in tunics of flesh - human or animal (generally mammal) bodies. Humans and other mammals were thus hybrid creatures belonging to two realms: a good potentially immortal spirit trapped inside a bad and corruptible body. This was one reason why Cathars refused to kill animals.

In some ways the idea reflected certain Buddhist beliefs. A person who lead a relatively good life might be reincarnated with a better and easier life the next time round. One who lived a bad life would be reincarnated further down the scale, possibly as an animal. Apparently even animals could live good or bad lives, because it was possible for an animal to be reincarnated as a human being. A popular Cathar story tells of a man who is overcome with emotion on recognising in the grass an iron shoe he had thrown in his previous life as a horse.

Those who eventually managed to lead a good enough life would be released from the cycle of rebirth. On their death the Bad God would loose his power over the angel trapped within. Released from their imprisonment, such angels would return to heaven, the realm of light to join the other angels there. They are there in the night sky for all to see. We non-believers call them stars.

Cathar ideas of Heaven and hell included a Fall from heaven, during which a number of angels were expelled from heaven and fell to earth. Here is an extract from Montana of Cremona, a Professor at the University of Bologna who became a Dominican - possibly an Inquisitor, though this is not known for sure. He is listing distinctively heretical beliefs - "What Heretics May Believe, or Rather, Concoct" around 1241-1244:

|

|

Few Catholics today would find this remarkable, since it is now Catholic orthodoxy. One of a number of examples of Catholic teaching adopting Gnostic and Cathar teachings.

According to some versions of Cathar theology the Fall of the Angels was slightly more complicated than this. The angels also had immaterial bodies which never left heaven. The Bad God had somehow stolen the souls from these angelic bodies and imprisoned them on earth to create human beings and other animals. On their release they were reunited with their angelic body in heaven.

|

Saint Michael weighing souls |

|

Hell

Hell, to the Cathars, was not a remote place under the Earth. For them Hell was here and now. The world itself, the creation of the Bad God, was the only Hell they knew. Torture, pain and misery of this life was all the Hell they needed to contemplate.

The objective for all Cathars was to escape from the cycle of reincarnation, to earn the right to return to heaven and avoid another term of imprisonment here in Hell on Earth. There was only one way to do this, and that was to be reunited with the Good God through the agency of the Holy Spirit. In certain defined circumstances the Holy Spirit would descend (as it had descended on Jesus) and release the soul. But the release was contingent. Until the person died, he or she, was obliged to continue trapped in a corporeal mantle, living a good life in an evil world.

The power to call down the Holy Spirit was conferred on an ascetic elite consisting of men and women who themselves had won their contingent release from the cycle of rebirth. These Parfaits (men) and Parfaites (women) alone could induce the Holy Spirit to descend and create another Parfait or Parfaite. This they did through a Cathar Ceremony called the Consolamentum. The requirements were rigorous and new Parfaits and Parfaites were expected to lives of the utmost purity,and from all the evidence did live lives of the utmost purity. They lived as Christian monks have always aspired to as an almost impossible ideal - extreme simplicity, poverty, strict adherence to the commandments, severe fasting, abstinence and deprivation, constant prayer, pacifism, the carrying out of good works, spreading the good word, and so on.

If they lapsed in any way they lost their status, their ability to pass on the gift of the Holy Spirit and their soul's place in heaven. Unless they underwent the Consolamentum again (which seems to have happened on a few occasions) they would be condemned to another life sentence in Hell here on earth.

|

The idea that hell extended to the Earth

was not confined to Cathars.

|

| "Hell is empty. All the devils are here" |

Some Cathars seem to have held that each soul could undergo at most seven or, according to some, nine incarnations. The question then arose as to what happened to those souls that failed to win their Consolamentum and release within the maximum number of cycles. Unfortunately we have no coherent answer to this. Our detailed information about Cathar belief comes largely from Catholic Inquisitors, and this was not a question they dealt with in detail.

For the Albigensian Crusaders and Inquisitors the Cathar idea of Hell was entirely mistaken. As they condemned hundreds of Parfaits and Parfaites to burn at the the stake, they recorded with evident pleasure (and "great joy") the certainty of their victims passing from the ephemeral flames of this world directly to the everlasting flames of the next.

|

The Catholic Conception of hell |

|

|

|

The Cathar conception of Hell - everyday life on Earth. (Detail of a miniature of the burning of

heretics. |

|

Other Teachings

Free agency lies at the core of the Italian Book of the Two Principles. The Cathars of the Languedoc, however, rejected the notion of free agency, and believed in predestination. Deprived of free agency, they considered that souls were predestined to be saved.

This is contrary to the Catholic doctrine of Free Will, but entirely consistent with the Lutheran and Calvinist doctrines of Predesination.

Cathar Prayer

The Cathars used mainly the "Pater" - Pater Noster - "Our father" - the only prayer prescribed in the New Testament. Click here for more on the The Pater

They did however use a form of greeting that resembles a simple prayer, the Melhoramentum. Click here for more on the Melhoramentum.

In their ceremonies they also used the Benedicite

Benedicite, Benedicite, Domine Deus, Pater bonorum spirituum, adjuva nos in ommibus quae facere voluerimus.

[Bless us, bless us, O Lord God, the Father of the spirits of good men, and help us in all that we wish to do]

The Cathar Pater

The Pater (or Lord's Prayer) was the favourite Cathar prayer - arguably their only prayer. It is, after all the only one sanctioned by the New Testament.

The Cathar Pater (from the �Cathar Ritual�)

Our father, which art in Heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done on Earth as it is in Heaven.

Give us this day our supersubstantial bread,

And remit our debts as we forgive our debtors.

And keep us from temptation and free us from evil.

Thine is the kingdom, the power and glory for ever and ever.

Amen.

Ordinary believers would not invoke God in this way. The prayer was reserved for Parfaits and Parfaites - who recited it on ceremonial occasions, including before a meal. The Cathar Consolamentum was not just a spiritual baptism, it was also a divine adoption ceremony. The new initiate literally became a child of God, and God became their father - conferring the right to address God as "Our Father".

Click on the following link for the Transmission

of the Pater (taken from the Traditio - the Lyons Ritual) in Occitan

and English

Click on the following link for the Rules

for the Use of the Prayer and Conduct Associated with its Recitation

(taken from the Traditio - the Lyons Ritual) in Occitan and English

The Doxology

Notice the final lines - a doxology - which will be familiar to Protestants but not to Catholics. These words were a sure sign of heresy to Catholic theologians and Inquisitors for many centuries. Here is a monk writing in about 1147 on the subject:

A most corrupt and secret aspect of their cult is that they do not say the [Roman Catholic] doxology but instead of "Glory be to the Father" say "For thine is the kingdom, and thou shalt rule over all creation, forever and ever. Amen"

Cathar texts give a slightly different version:

For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, forever. Amen

Cathars claimed that the words they used were in the original versions of the text of Matthew 6:13. Here is an extract from a Cathar ritual explaining the Lord's Prayer, line by line:

'For thine is the kingdom'. This phrase is said to be in the Greek and Hebrew texts...

The Catholic Church denied that these words should be included as they were not to be found in the Vulgate - a fifth century translation into Latin by St Jerome, which the Roman Catholic Church regarded as infallible. In fact the phrase is to be found in early Greek texts and in Slavonic texts - confirming that the Cathars really did have links to the early Church and suggesting that those links were Bogomil.

The oldest witness is the Didache, otherwise known as the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles. This ancient catechism dates to the early second century, perhaps shortly after 100 AD (ie much earlier than the texts used to justify omitting the text in question).

Do not let your fasts be with the hypocrites. They fast on Monday and Thursday; but you shall fast on Wednesday and Friday. Do not pray as the hypocrites do, but as the Lord commanded in His gospel, you shall pray thus: 'Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts, as we also forgive our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. For thine is the power and the glory forever.' Pray thus three times a day.

|

The quotation here is from the Writings of a Cistercian monk from Périgueux named Herbert. The translation is from Walter Wakefield & Austin Evans, Heresies of The High Middle Ages (Columbia, 1991) p 139 from Herbiberti monachi epistola de haereticis Petragoricis reproduced in Migne, Patrologia latina, CLXXXI, 1721-22. For the Cathar doxology in Greek and Slavic versions of the bible see Runciman, The Medieval Manichee: A study of the Christian Dualist Heresy, Cambridge, 1955, p 166 The question of the Cathar doxology was discussed by Medieval theologians (eg Antoine Dondaine, UN Traité neo-manichéen du XIIIe siècle: Le Liber de duobus principiis, suivi d'un fragment de rituel Cathare. Rome, 1939, p48 and Arno Borst, Die Katharer (Schriften der Monumenta Germaniae historica, XII), Stutgart, 1953, p191. The translation of the Didache is from W. A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1970), 3.). There are numerous early witnesses : It is found in the Old Latin, the Old Syrian, and some Coptic versions (such as Coptic Bohairic). Old Latin texts, such as Codices Monacensis (q-seventh century) and Brixianus (f-sixth century), read, "et ne nos inducas in temptationem. sed libera nos a malo. quoniam tuum est regnum. et uirtus. Et gloria in saecula. amen." The Syriac Peshitto (second to third century) reads, "And bring us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever and ever: Amen." (James Murdock, The Syriac New Testament from the Peshitto Version [Boston: H.L. Hastings, 1896], 9.) Among the Greek uncials it is found in K (ninth century), L (eighth century), W (fifth century), D (ninth century), Q (ninth century), and P (ninth century). It is found in the following Greek minuscules: 28, 33, 565, 700, 892, 1009, 1010, 1071, 1079, 1195, 1216, 1230, 1241, 1242, 1365, 1546, 1646, 2174 (dating from the ninth to the twelfth century). The Church Father John Chrysostom was also familiar with it. He cites the verse in the fourth century in his Homilies: ". . . by bringing to our remembrance the King under whom we are arrayed, and signifying him to be more powerful than all. 'For thine,' saith he, 'is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory.'" (St. Chrysostom, "Homily XIX," in The Preaching of Chrysostom, ed. Jaroslav Pelikan [Philadelphia: Fortress Press], 145.) |

The validity of the Cathar version is endorsed by the Anglican Church which also follows the early Greek texts and includes the phrase translated in the Authorized Version as "For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, forever. Amen" - the same as formulation as that used by some Cathar texts. The passage is also found in Spanish, French, Italian, and German versions which pre-date the Authorized (or King James) version. Early English versions such as the New Testament of William Tyndale (1525) also have it: "And leade us not into temptacion: but delyver us from evyll. For thyne is the kingdome and the power, and the glorye for ever. Amen."

|

The Lord's Prayer in the original Kione (Greek) with the word ἐπιούσιον meaning "supersubstancial" not "daily", and the doxology in brackets.

|

|

Πάτερ ἡμῶν

ὁ ἐντοῖς οὐρανοῖς� |

|

The Pater Noster - Our Father in Latin

|

|

Pater noster qui es in celis, |

|

Another Cathar Prayer

|

|

Daily Bread ?

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence that the Cathars preserved a very ancient tradition - earlier than the that represented by modern mainstream Christian Churches - is the treatment of the word rendered in the Latin text above as "supersubstancialem". The original Greek word is επιουσιον and the interesting thing about it is that no one knows for sure what it means. One thing for sure is that it does not mean "daily", which is how mainstream Churches translate it (..Give us this day our daily bread"). More interesting yet is the fact that the Cathars, and the Bogomils before them, appear to have preserved the meaning of the original Greek - and more remarkable still is the fact that the original meaning was known to the early Church reformers in England.

If you find this extraordinary, as I do, you might want to read on. (If not, you may find it hard going). The text below is taken from the Etudes balkaniques, 2001, No1, which deals in detail with the whole question - (With thanks to Georgi Vasilev, Ph.D., D.Sc. see https://www.geocities.com/bogomil1bg):

JOHN WYCLIFFE, THE DUALISTS AND THE CYRILLO-METHODIAN VERSION OF THE NEW TESTAMENT

1. Our bread over another substance [ouer bread over othir substaunce]

... Open any modern official edition of the Bible in English (for example The Holy Bible. New Revised Standard Version. Oxford, 1989) and read the Lord�s Prayer and you shall see that there God is asked to give [us] �this day our daily bread�. In Wycliffe�s English versions of the Scriptures however, begun about the year 1380, one finds a rather different text, i.e. �oure breed ouer othir substaunce� Math. 6:9-13 [give us this day our daily bread over another substance] {9}. Why the difference? Why such an unusual sounding in which, besides the translation, there is obviously a small comment of the translator himself? The answer on principle was provided by Yordan Ivanov, a noted Bulgarian philologist and historian. In his well-known book, Bogomil Books and Legends, he wrote that the Bosnian Bogomils read the Lord�s Prayer in just such a way, pronouncing �give us our daily bread of another substance� {10}. A similar version can be found in the lyonnaise rendition of the Albigensian Scriptures: �E dona a noi lo nostre pa qui es sabre tota cause� [�the bread that is above all else�]. Similarly there is one Old Italian version: �Il pane nostre sopra tucte le substantie da a nnoi oggi� [�our bread over any substance�].

Since the Bogomils gave the Cathars the quoted version of the Cyrillo-Methodian translation of the New Testament (subsequently translated into the Latin by the Cathars), we shall turn to the idea that John Wycliffe did not translate the Scriptures from the Vulgate, as the printed editions of his version later stated, but from a Cyrillo-Methodian version. By the way, even today the Bulgarian version of the Lord�s Prayer reads �our daily [substantial] bread� which is much closer to the Greek original �τον̣ αρτον ημον τον επιουσιον where the word �επιουσιον� means literally �suprasubstantial�. In other words, the Cyrillo-Methodian version is closer to the Greek original than the Vulgate �our daily [quotitianum] bread�. In fact, the term �supersubstantialem� is used in the various Vulgate versions, in Matthew and in Luke (11:2-4), but it is practically excluded from the liturgical and sacramental practice of the Catholic Church. What is more, to pronounce �suprasubstantial� [supersubstantialem] instead of �our daily bread� [panem nostrum quotidianum] in the Lord�s Prayer was considered a sure sign of heresy in the Middle Ages. According to Collectio Occitanica, Inquisition records from Carcassonne, in Lombardy Bernard Oliva, the heretical bishop from Toulouse, pronounced 'panem nostrum supersubstantialem' (dicendo in oratione Pater noster: panem nostrum supersubstantialem) when he said the Lord�s Prayer{11}.

Even in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, many authors paid attention to the fact that the Bogomils lay the stress on �our bread of another substance�.

In this case we shall list just a few of them because, both in Bulgaria and abroad, one encounters a conservative underestimation of this detail and an inability to decipher its theological significance {12}. H. Puech and A. Vaillant underscored the concept described by Euthymius Zygavin that �Bogomils created their haven, the true eucharistic bread that is "αρτος επιουσιος�, by which they acquire the blood and flesh of Christ everyday" {13}. Zygavin mentions the special word "επιουσιος" by which they characterised the bread: "τον̣ αρτον γαρ, φηςι, τον επιουσιον� {14}. N. Osokyn also noted the �Greek practice� of the Bogomils and the Cathars: they sang the Lord�s Prayer after the Greek fashion, substituting �our daily bread� (quotidianum) for the words �our supernatural bread� and adding at the end ���� ���� ��� �������� etc. adopted by the Eastern Church with good reason� {15}. Jean Guiraud, a scholar who studied the Cathars and was their opponent centuries after they existed, claimed that �they dared to adjust even the word of Christ�, taking the liberty to read the said part of the Lord�s Prayer in their own way {16}.

At this point I would like to undertake a rather more comprehensive explanation of the Cathar concept of the Lord�s Prayer that C. Schmidt made in 1849: �... they interpreted �daily bread� in the sense of food for the soul and, instead of the simple formula from the Scripture, �Give us today our superstubstantial bread�, ending with the words �for Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory in all eternity�. Since these words cannot be found in the Vulgate, the opponents of the Cathars who were not familiar with the original text, accused them of misrepresenting the Bible in this particular place. This accusation the latter did not deserve because on this point their version, made on the basis of a Greek source, was more correct than the version of the Western Church.� {17}

It was exactly Schmidt who gave the explanation, repeated a century later by Yordan Ivanov. He pointed out that, in the Greek original, the expression from Matthew �τον̣ αρτον ημον τον επιουσιον� repeated also in Luke, was translated as panem supersubstantialem (Matthew) and panem quotidianum (Luke) in the Vulgate. He added that the latter expression �was more accepted in the [Catholic � author�s note] Church than the former one� {18}.

FOOTNOTES

9. The Holy Bible, made from the Latin Vulgate by John Wyccliffe and his followers, vol. IV, p. 18.

10. ������, �. ���������� ����� � �������. �����. 1925, �.113. The same fact is quoted in "Slovnίk jazyka staroslověnskeho. Lexicon linguae palaeslovenicae. t .II, p.322: "�����������" (Tetra-evangelium Nikojanum, Serbia XV, Cyr. Num.indicis A.-23).

11. D�llinger, Ign. V. Dokumente vornehmlich zur Geschichte der Valdesier und Katharer herausgegeben. Munchen. T. II. M�nchen, 1890, S. 38: �...dicendo in oratione Pater Noster: panem nostrum supersubstantialem�. This case was also quoted by Y. Ivanov.

12. One should mention here that there are only a few good interpretations of Bogomil and Cathar theology, including Raicho Karolev�s 19th century work, those of H. Puech and A. Vaillant, as well as Edina Bozoki, among others. In the case of Bulgaria, the cause was the fact that, after 1944, research of the Bogomil movement fell under Marxist interpretation, with their teaching seen above all as a social moevement. In the West, powerful Catholic influence was a barrier before studies of the finer peculiarities of dualistic philosophy. There is not s single study in this sense in Great Britain.

13. Puech, H. A. Vaillant. Le traite contre les Bogomiles de Cosmas le Pr�tre. Paris. 1945, p. 245.

14. Patrologia Graeca, 130, col. 1313.

15. ������� �. �����i� ����������� �� ������� ���� ��������i� III. T. I. ������, 1869, �. 214.

16. Giuraud, J. Cartulaire de Notre Dame de Prouilles, pr�c�d� d�une �tude sur l�Albigeisme languedocien au XIIe et XIIIe siecles. T. 1-2. Paris. 1907, p. CXXII.

17. Schmidt, C. Histoire et doctrine de la secte Des cathares ou albigeois. T. II. Paris-Geneve. 1849, p. 117.

18. Ibidem.

A Cistercian writes:

Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay in his Historia Albigensis written

between 1212 and 1218, describes cathar beliefs:

English translation based on Peter of les Vaux-de-Caernay (translation by WA Sibly and MD Sibly, The History of the Albigensian Crusade (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2002) p10-11. There is another translation at Wakefield & Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, p 238. The webmaster has marked particularly interesting points in red). Here the Cathars are presented as Docetes and Dualists who regard Jehovah, the lying murderous God of the Old Testament, as the evil God (opposed to the God of the New Testament who is the good God).

[10] First, it should be known that the heretics [the Cathars] propose the existence of two creators, one of things invisible, whom they call the benign God, and one of things visible, whom they name the evil God.

They attribute the New Testament to the benign God and the Old to the malign God, and they repudiate all of the Old Testament except for certain passages included in the New Testament, which they judge to be appropriate because of their respect for the New Testament. They assert that the author of the Old Testament is a liar, for he said to the first created man: "But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die" [Genesis 2:17], yet they did not die after eating of it, as he had said they would-though in reality after eating of the forbidden fruit they became subject to death. They also called him a murderer because he incinerated the people of Sodom and Gomorrah, destroyed the world by the waters of the Flood, and overwhelmed Pharaoh and the Egyptians with the sea.

They declared that all of the patriarchs of the Old Testament were damned; they asserted that John the Baptist was one of the greatest devils.

[11] And they also said in their secret meetings that the Christ who was born in the earthly and visible Bethlehem and crucified in Jerusalem was evil; and that Mary Magdalene was his concubine; and that she was the woman taken in adultery of whom we read in Scripture [John 8:3].

Indeed, the good Christ they say neither ate nor drank nor assumed the true flesh, nor was he ever in this world except spiritually in the body of Paul. But for this reason we say "in the earthly and visible Bethlehem": The heretics believe there to be another earth, new and invisible, and in this second earth some of them believe the good Christ was crucified.

Likewise, the heretics say the good God had two wives, Colla and Colliba, and from these he begat sons and daughters.

There were other heretics who said that there was one Creator, but that he had as sons both Christ and the Devil.

They said that all creatures were once good but that from the vials of which we read in the Apocalypse [Revelation 16:1-21], all were corrupted.

|

|

|

they asserted that John the Baptist was one of the greatest devils. This is not recorded elsewhere, but seems an oddthing for Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay to make up.

|

|

Mary Magdalene was his concubine. An ancient Gnostic belief.

|

|

the good God had two wives, Colla and Colliba, and from these he begat sons and daughters. Colla and Colliba (given in some translations as Collant and Colibant), are probably identical with Oolah and Ooliba (Aholah and Aholibah) the sister-whores from Ezekiel 23:4 who symbolize Israel and Judah and are described as brides of God. But wouldn't they be wives of the bad God? Perhaps Pierre has misunderstood.

|

|

there was one Creator, but that he had as sons both Christ and the Devil. This reporting of alternative versions lends credibility. If Pierre were making it up, he would have no reason to make up variations of the story. This one looks like a popular attempt to reconcile Cathar and Catholic beliefs. |

Further Information on Cathars and Cathar Castles

|

If you want to cite this website in a book or academic paper, you will need the following information: Author: James McDonald MA, MSc.

If you want to link to this site please see How to link to www.cathar.info

For media enquiries please e-mail james@cathar.info

|

| CATHAR BELIEFS | CATHAR WARS | CATHOLIC CHURCH | CATHAR INQUISITION | CATHAR CASTLES | CATHAR ORIGINS | CATHAR LEGACY | CATHAR TOURS | CATHAR BOOKS | WHO's

WHO |

CATHAR TIMELINE | MORE INFO |

CATHAR GLOSSARY | CATHAR NEWS |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| :::: Link to www.cathar.info ::: © C&MH 2010-2016 ::: contact@cathar.info ::: Advertising ::: |