Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the Languedoc

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Who's Who In The Cathar War

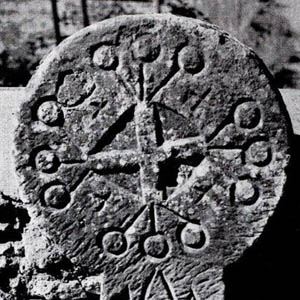

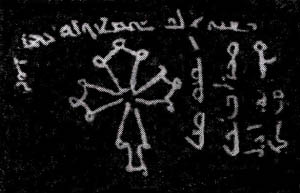

The Catholic Side: Crusade Leaders and their Allies The "Cathar" Side: Opponents and Victims of the Crusade. Heraldry of the Cross of Toulouse

The following are the chief personalities during the Wars against the Cathars:

Crusade Leaders and their Allies

Pope Innocent III: Called the crusade in 1208. Click here for more on Pope Innocent III Arnaud Amaury: Cistercian Abbot of Cîteaux. Military commander of the crusade in its early stages. Click here for more on Arnaud Amaury. Bernard of Clairvaux (Saint Bernard): Cistercian

Abbot who had tried to combat "heresy" in Toulouse and

the Languedoc by preaching against it in the century before the

Crusade. Click here for more on Bernard

of Clairvaux Simon de Montfort: Titular Earlof Leicester, and

lord of Montfort. Took over leadership of the Cathar Crusade

after the initial victories at Béziers

and Carcassonne.

Click here for more on Simon

de Montfort Amaury de Montfort: Earl of Leicester. Took

over leadership of the Cathar Crusade after the death of his father

Simon. Click here for more on Amaury

de Montfort Dominic Guzmán (Saint Dominic): A preacher

who set up the religious order ("The Dominicans")

which established and ran the first papal Inquisition.

Click here for more on Dominic

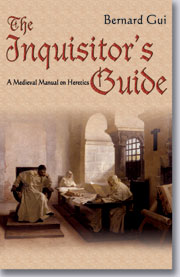

Guzmán Bernard Gui: A Dominican

Inquisitor who left a useful manual for identifying and punishing

Cathars and other supposed "heretics". Click here for

more on Bernard

Gui Philippe Augustus: King of France. Requested by Pope Innocent III to lead a crusade against the Cathars of the Languedoc. Eventually allowed his vassals and later still his son to join the Crusade. Click here for more on Philippe Augustus Louis VIII: King of France. Joined the Cathar Crusade and later led it. Click here for more on Louis VIII Blanche of Castile: (1188-1252). Regent of France (1226-36) during the infancy of her son Louis IX, King of France. Click here for more on Blanche of Castile Louis IX: King of France, also known as Saint Louis, a Crusader King. Click here for more on Louis IX Guy and Pierre Des Vaux-de-Cernay. A Crusading Cistercian

Abbot (Guy) and his nephew (Peter), a monk who left an invaluable

record of the Crusaders actions and their beliefs. Click on the

following link for more on Pierre

Des Vaux-de-Cernay and his Historia

Albigensis Fulk (or Folquet) de Marseille: A troubadour who

later became Bishop of Toulouse. Click here for more on Fulk

de Marsielle Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers: (c 1280 -

1342) Famous for his Inquitation records which survived in the Vatican

Archives after he was elected Pope as Benedict XII. Click here for

more on Jacques

Fournier

Opponents and Victims of the Crusade.

Peter II: (1174-1213) King of Aragon (1196-1213). Close relative and ally of the Counts of Toulouse. Recognised as the greatest Crusader in Christendom at the time, but opposed to the Crusade against his own vassals. Click here for more on Peter II: Raymond VI: (1156-1222), Count

of Toulouse (1196-1222). Click here for more on Raymond

VI

Raymond VII: (1197-1249), Count of Toulouse

(1222-1249). Click here for more on Raymond

VII Raymond-Roger Trencavel: (1184-12093). Viscount of

Carcassonne.

Relative of the Counts

of Toulouse. Click here for more on Raymond-Roger

Trencavel Raymond Trencavel II: (1204-126). Viscount of

Carcassonne. Son of Raymond-Roger. Click here for more

on Raymond

Trencavel II Raymond Roger: Count of Foix (1188-1223). Click here

for more on Raymond

Roger Roger Bernard II: Count of Foix (1223-1241). Click

here for more on Roger

Bernard II Roger IV: Count of Foix (1241-1265). Click here for

more on Roger

IV Savaric de Mauléon: ( Count of Comminges: Vassal and ally of the Counts

of Toulouse. Click here for more on Count

of Comminges Viscount of Béarn: Vassal and ally of the

Counts

of Toulouse. Click here for more on Viscount

of Béarn Esclarmonde of Foix:

Parfaite.

Click here for more on Esclarmonde

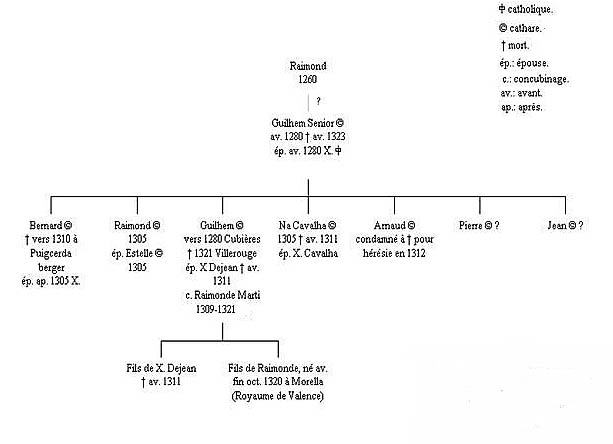

of Foix Guilhem Belibaste: (c 1280 - 1323) The last known

Cathar Parfait

in the Languedoc, burned at the stake in 1323. Click here for more

on Guilhem

Belibaste

Click on the following link for the Fransiscan friar Bernard

Delicieux Click on the following link for the

heraldry of the Crusade leaders, and other nobles |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

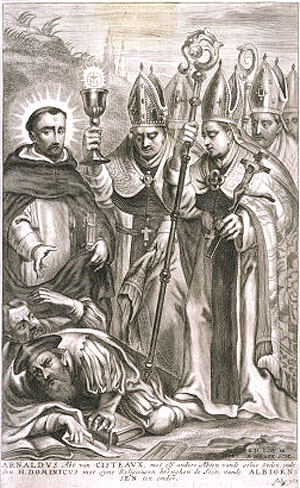

Arnaud Amaury (Latin: Arnaldus Amalricus,

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

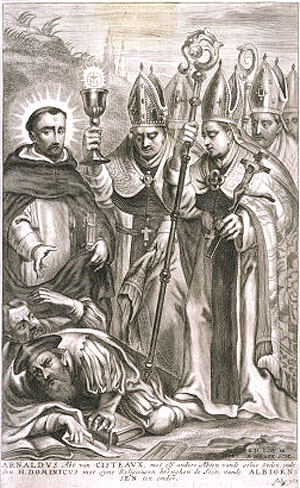

Arnaud

Amaury, other Cistercian abbots and St-Dominic.

(with a halo) crush helpless Cathars underfoot - a sanitised

version of the persecution of the Cathars. |

|

|

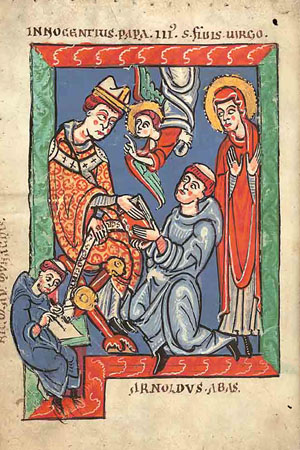

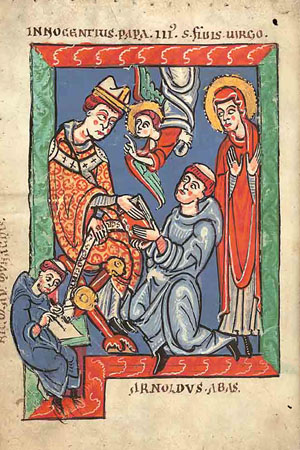

Pope

Innocent III with Cistercian

abbot Arnaud

Amaury |

|

|

Béziers where the Abbot-Comander Arnaud Amaury reported having killied 20,000 without regard to age, sex or rank, having given the order "Kill Them All, God will know his own" |

|

|

|

Simon IV de Montfort (1160 - 25th June, 1218)

Simon de Montfort succeeded his father as Baron de Montfort in 1181. In 1190 he married Alix de Montmorency, the daughter of Bouchard III de Montmorency.

In 1191 Simon's brother, Guy de Montfort, left on the Third Crusade in the retinue of King Philip II of France. In 1199, while taking part in a tournament at Ecry-sur-Aisne, Simon heard Fulk of Neuilly preaching the Fourth Crusade. Along with Count Thibaud (Theobald) de Champagne, he took the cross as did his brother Guy. The crusade was diverted by a Cardinal to the Christian city of Zara on the Adriatic Sea. The city was sacked and plundered in 1202. Simon did not participate in the sacking, and soon he left the Crusade, continuing to the Holy Land. (His fellow Crusaders went on to sack the city of Constantinople).

At the time of the Cathar Crusade, Simon had already built a reputation. He was a rare commodity within the Catholic fold. He was not only a fearsome warrior, but also a good tactician and strategist. Further, he had distinguished himself in the Fourth Crusade by refusing to attack his fellow Christians in Byzantium.

In 1209 he found himself among the army assembled under the Abbot of Cîteaux to attack the Cathars of the Languedoc. After the initial victories at Béziers and Carcassonne the nobles looked for one of their number to take over the leadership. None of them was prepared to take on what appeared to be an impossible task, especially as it involved a feudal dispossession that many considered not only illegal but also a dangerous precendent. As Simon had distinguished himself once again in battle he was offered the leadership and effectively ordered to accept it. Simon had no choice. He accepted and over the following nine years confirmed his reputation for tactical brilliance.

|

![]() The Church awarded Simon territory

conquered from Raymond VI of Toulouse. Simon became known

and feared for his cruelty and for his "treachery, harshness,

and bad faith." In fairness he was often acting in obedience

to Church orders, as in 1210 when he burned 140 Cathars

alive in the village of Minerve.

He was a man of extreme Catholic orthodoxy, committed to the Dominican

Order and to the suppression of what he believed to be heresy.

The Church awarded Simon territory

conquered from Raymond VI of Toulouse. Simon became known

and feared for his cruelty and for his "treachery, harshness,

and bad faith." In fairness he was often acting in obedience

to Church orders, as in 1210 when he burned 140 Cathars

alive in the village of Minerve.

He was a man of extreme Catholic orthodoxy, committed to the Dominican

Order and to the suppression of what he believed to be heresy.

He led the Crusader army at Termes 1210, Lavaur 1211, Toulouse 1211, and Castelnau 1211. In 1213 his Crusader army defeated Peter II King of Aragon at the Muret. The southern armies were now crushed, but Simon carried on the campaign as a war of conquest, being appointed lord over all the newly acquired territory with Raymond VI's titles as Count of Toulouse and Duke of Narbonne (1215).

![]() From 6 June 1216 to 24 August 1216

he besieged Beaucaire,

which had been taken by his son Raymondet (later Raymond

VII of Toulouse). Responding to rumours that Raymond VI was on his way to Toulouse

in September 1216, Simon abandoned the siege

of Beaucaire, and sacked the city of Toulouse.

Raymond returned to take possession of Toulouse

a year later in October 1217 and Simon again hastened to the city,

this time to besiege it.

From 6 June 1216 to 24 August 1216

he besieged Beaucaire,

which had been taken by his son Raymondet (later Raymond

VII of Toulouse). Responding to rumours that Raymond VI was on his way to Toulouse

in September 1216, Simon abandoned the siege

of Beaucaire, and sacked the city of Toulouse.

Raymond returned to take possession of Toulouse

a year later in October 1217 and Simon again hastened to the city,

this time to besiege it.

After maintaining the siege for nine months Simon was killed on 25 June 1218. His head was smashed by a stone from a mangonel operated by the women of Toulouse - "donas e tozas e mulhers" (noblewomen, little girls and men's wives). He was initially buried in the Cathedral of Saint-Nazaire at Carcassonne but his body was soon removed to his home in France.

In the nineteenth century the Capitouls of Toulouse commissioned a series of historical murals. One of them shows a lion representing Simon de Montfort pierced through the body by a pole surmounted by the cross of Toulouse.

![]()

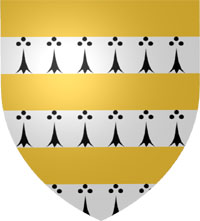

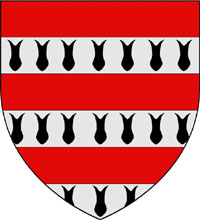

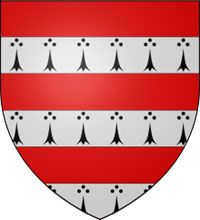

![]() The symbolism is drawn from the arms

of the Montfort and Toulouse. The banner reads "Montfort is

dead. Long live Toulouse (Montfort est mort. Viva Tolosa). It is

a striking image and suggests a strong identification with Count

Raymond against Simon.

The symbolism is drawn from the arms

of the Montfort and Toulouse. The banner reads "Montfort is

dead. Long live Toulouse (Montfort est mort. Viva Tolosa). It is

a striking image and suggests a strong identification with Count

Raymond against Simon.

Simon left three sons and two daughters:

- Amaury de Montfort, his eldest son, who inherited his French

estates. Click here for more about Amaury

de Montfort

- Guy de Montfort, (named after his uncle Guy de Montfort) who married Petronille, Countess of Bigorre, on 6 November 1216 - an attempt to build a family dynasty in Occitania. He died at the siege of Castelnaudry on 20 July 1220.

-

Simon

de Montfort, who eventually gained possession of the earldom of

Leicester (previously appropriated by King

John of England) because of the de Montfort family's allegiance

to the King of France. This Simon not only regained the

Earldom but played a leading role in establishing parliamentary

rights in England in the reign of Henry

III. He has been called "The father of parliament".

A plaque to him adorns a wall in the US House of Representatives.

In recent years a British university has been named after him,

and he is remembered with great honour to this day, a polar opposite

of his father who left only a legacy of bitterness and hatred.

Simon

de Montfort, who eventually gained possession of the earldom of

Leicester (previously appropriated by King

John of England) because of the de Montfort family's allegiance

to the King of France. This Simon not only regained the

Earldom but played a leading role in establishing parliamentary

rights in England in the reign of Henry

III. He has been called "The father of parliament".

A plaque to him adorns a wall in the US House of Representatives.

In recent years a British university has been named after him,

and he is remembered with great honour to this day, a polar opposite

of his father who left only a legacy of bitterness and hatred. - Petronilla became Abbess at the Cistercian nunnery of St. Antoine's.

- Amicie (or Amicia) named after her grandmother, founded the nunnery at Montargis and died there in 1252.

Click here for more about the heraldry and genealogy of Simon

IV de Montfort and other Crusader nobles ![]()

Click on the following link for more on the

Seal of Simon de Montfort ![]()

Click here for more about the heraldry and genealogy of Simon's

brother Guy

de Montfort ![]()

Click here for more about the heraldry and genealogy of Simon's

son Amaury

de Montfort ![]()

Click on the following link for more on the

Seal of Simon de Montfort ![]()

|

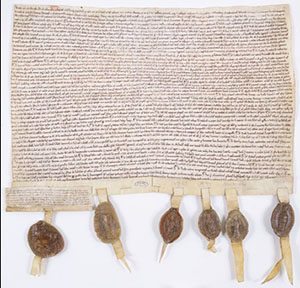

The Counts of Toulouse issued charters promising their subjects protection, justice and respect for established custom a generation before Magna Carta. The statute of Pamiers, imitating this tradition, was issued at Pamiers, near Toulouse, in December 1212 by Simon de Montfort. In this charter Simon styles himself as Earl of Leicester (comes Leyc’) and also Vicomte of Beziers and Carcassonne, and lord of Albi and the Razès. This charter, sealed and guaranteed by half a dozen French bishops, includes more than 50 clauses, prohibiting the sale of justice, dealing with the rights of heirs and widows, and promising not to demand military service from his tenants save by grace and in return for pay. Ten of its 11 opening clauses guarantee freedoms to the Church. Attached to it is a letter commanding publication, sealed by Simon himself. Many of the Statute of Pamiers’s clauses deal with problems also addressed by Magna Carta. It was almost certainly known in England. Several English knights fought in Simon’s army, including Walter Langton, brother of the Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1212 the English barons planned to depose King John and to make Simon de Montfort king in his stead. Simon’s son, another Simon (1208-65), would later become leader of an English baronial rebellion. In 1265, 50 years after Magna Carta, the younger Simon played a crucial role in the emergence of the English Parliament. |

|

|

Statue of Simon de Montfort on the Haymarket Memorial Clock Tower in Leicester. This is the son of Simon de Montfort the Albigensian Crusader. |

|

|

||||||

|

Simon IV de Montfort Buste par Jean-Jacques Feuchère, Galerie des batailles, Versailles |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Photograph of Simon's tombstone at Carcassonne,

with the contrast increased |

||||||

|

||||||

|

On his surcoat (technically his "coat

of arms")

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Seal of Simon IV de Montfort. Click on the following link for more on the Seal of Simon de Montfort. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

The death of Simon de Montfort at Toulouse in 1218. Illustration by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville from François Guizot (1787-1874), The History of France from the Earliest Times to the Year 1789, London : S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1883, p. 515 |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

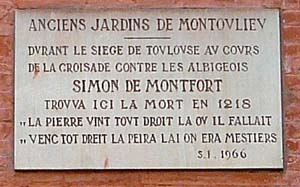

Today, the spot where Simon de Montfort met his end is marked by a plaque set into a wall of pink Toulouse brick (see left). It reads: "Old Montoulieu Gardens - During the siege of Toulouse in the course of the Albigensian Crusade Simon de Montfort was killed here in 1218". The last two lines are a quotation from the Song of the Cathar Wars, laisse 205, cited above: both read "now a stone hit just where it was needed" first in French then in the original Occitan. |

||||||

|

Simon was roundly hated in the Languedoc for his cruelty and ambition. Here is a description of his death from the contemporary Song of the Cathar Wars, laisse 205, written in Occitan:

|

Ac dins una peireira, que fe us carpenters |

There was in the town a mangonel built by our carpenters |

Simon de Montfort left few friends in the lands he pillaged and tried to rule. He continues to be hated to this day. The consensus is that the writer of the Song of the Cathar Wars had it about right [laisse 208]. His scathing words about Simon's glowing epitaph in the Cathedral of St Nazaire (now the Basilica of Saint-Nazaire) in Carcassonne are given below:

|

E ditz e l'epictafi, cel qui•l sab ben legir, |

The epitaph says, for those who can read it,

That he is a saint and martyr who shall breathe again And shall in wondrous joy inherit and flourish And wear a crown and sit on a heavenly throne. And I have heard it said that this must be so - If by killing men and spilling blood, By wasting souls, and preaching murder, By following evil counsels, and raising fires, By ruining noblemen and besmirching paratge, By pillaging the country, and by exalting Pride, By stoking up wickedness and stifling good, By massacring women and their infants, A man can win Jesus in this world, then Simon surely wears a crown, resplendent in heaven. |

Click here to learn about the untranslatable Occitan word paratge

Amaury VI de Montfort

![]() Amaury

VI de Montfort (1195-1241) was the son of Simon de Montfort and

Alice of Montmorency, and the elder brother of another Simon de

Montfort.

Amaury

VI de Montfort (1195-1241) was the son of Simon de Montfort and

Alice of Montmorency, and the elder brother of another Simon de

Montfort.

Amaury de Montfort accompanied his father Simon and mother Alix de Montmorency on the Crusade against the gathers. He was just a boy at the beginning of the war, but was 18 and ready to become a knight by 1213. His knighthood was notable as it marked an important transition. Making a knight had been a rough-and-ready secular ceremony, but Simon turned the ceremony into a religious one, performed during a mass at the alter, and referring to passages in the Old Testament where God requires the first born to be dedicated to him. From now on knighthood would have a more distinctive Christian character. The following account comes from the Historia:

[429] …I will describe in detail the the procedure used for the Count's son's installation as a knight of Christ, since it was new and without precedent.

[430]The Count's eldest son becomes a knight. In the year of the Incarnation of the Word 1213, the noble Count of Montfort and numerous of his barons and knights gathered together at Castelnaudary on the feast of the nativity of John the Baptist [24 June]. The Count was accompanied by the two venerable bishops [of Auxerre and Orleans] and some crusader knights. Our most Christian Count wished the Bishop of Orleans to appoint his son a knight of Christ and personally hand him the belt of knighthood. The bishop for some time resisted this request but was at length vanquished by the prayers of the Count and our people, and yielded to their request. As it was summertime and Castelnaudary was too small to hold the huge crowd in attendance (not least because it had previously been destroyed once or even twice) the Count had a number of pavilions erected on a pleasant level place nearby.

[431] On the day of the feast the Bishop of Orleans donned his robes of office to celebrate a solemn mass in one of the pavilions. Everyone, knights as well as clergy, gathered to hear the mass. As the Bishop stood at the alter performing the mass, the Count took Amaury, his eldest son, by his right hand, and the Countess by his left hand; they approached the alter and offered him to the Lord, requesting the Bishop to appoint him a knight in the service of Christ. The Bishops of Orleans and Auxerre, bowing before the alter, put the belt of knighthood round the youth, and with great devotion led the Veni Creator Spiritus. Indeed a novel and unprecedented form of induction into knighthood! Who that was present could not refrain from tears? In this way, with great ceremony, Amaury became a knight.

(Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay, translated by WA & MD Sibly, The History of The Albigensian Crusade)

Simon died on 25th June 1218 while besieging Toulouse. During a typically brave action to retrieve a siege engine called a "cat" he was struck full on the head by a stone from a trebuchet, traditionally claimed to have been operated by the women of Toulouse. Amaury had participated in the Albigensian Crusade under his father's command. Now he inherited the County of Toulouse, and was elected as the new leader of the Crusade, as the people of the Languedoc celebrated his father's death.

Amaury could not fill his father's shoes. Only with the help of France could he avoid utter defeat. Amaury ceded formal rights to his territories to King Louis VIII in 1224. He removed his father's body from the Cathedral at Carcassonne (probably fearing what would happen to it if he left it there) and took it with him to his ancestral home near Paris.

In 1230 Amaury became Constable of France, an office previously held by his uncle Mathieu II of Montmorency.

In 1239 he participated in the Sixth Crusade and was taken prisoner after the defeat at Gaza. He was imprisoned in Cairo and was freed in 1241, but died the same year in Calabria while on his way home.

|

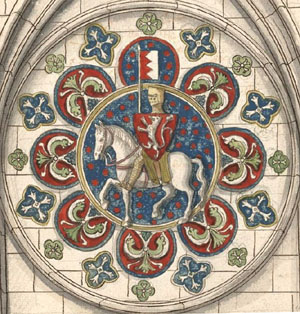

Amaury VI de Montfort, based on the image in Chartres Cathedral ? |

|

|

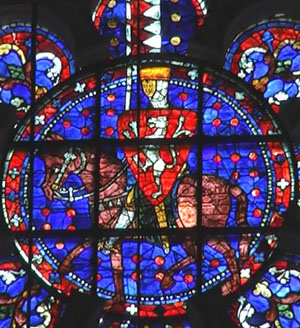

Amaury VI de Montfort, Chartres Cathedral |

|

|

Amaury VI de Montfort, Chartres Cathedral |

|

|

Amaury VI de Montfort by Henry Scheffer (1798-1862) |

|

Dominic Guzmán (c 1170 - 1221)

"Saint Dominic" (1234)

Dominic Guzmán, came from Caleruega in Castile. His parents, Felix Guzmán and Joanna of Aza, belonged to the nobility of Spain. According to later stories, his birth and infancy were attended by many marvels forecasting his great sanctity. In 1184 Saint Dominic entered the University of Palencia, where he remained for ten years. We do not know the date of his ordination, but he became a cannon of the Cathedral of Osma in 1195.

Passing through the Midi on his way back from Denmark in 1205 he started preaching against the Cathars of the Languedoc. He had planned, (with the help of God, he said) to convert Cathars to the Roman faith by preaching to them. Despite God's help his preaching proved a failure.

Spurred by his lack of success he hit on the idea of using schools to teach people the Catholic faith - one of many ideas he was to copy from the Cathars. At this time the Catholic Church did not normally encourage education for the laity, and indeed actively discouraged it, especially for women. But the Languedoc was a special case. Dominic founded a convent at Sainte Marie de Prouille (near to Fanjeaux), a Catholic version of a Cathar convent at Dun (between Pamiers and Mirapoix) founded by Philippa, wife of the Count of Foix. Dominic's establishment was in effect the first Dominican nunnery.

The Church also tried open debates as a way of winning converts. Debates were permitted because the Roman clergy thought that they could humiliate the opposition intellectually and so facilitate mass defections to the Roman Church. This did not happen.

The Colloquy of Montr�al in 1207 was the final debate in Pamiers between the Catholics (represented by Dominic Guzmán) and the Cathars (notably Beno�t de Termes). Once again the the Roman Church made no progress, and if anything confirmed its role as a figure of fun and reservoir of ignorance and bigotry. When a highly respected noblewoman, Esclarmonde of Foix (the Count's sister), a Parfaite, tried to speak she was admonished by one of Dominic Guzmán's acolytes (Etienne de Metz): "go to your spinning madam. It is not proper for you to speak in a debate of this sort". Such attitudes voiced in front of a liberal educated audience succeeded only in confirming the extent of the gulf between the Roman Church and the general population of the Languedoc. In any case, even with God's personal help, the Roman Church once again failed to secure mass conversions, or indeed any conversions at all among the Parfaits.

Guzmán was humiliated by his failure. More vigorous action was called for. The great Bernard of Clairvaux (St Bernard) had asserted that "The Christian glories in the death of a pagan, because Christ is thereby glorified". Were not heretics even worse than pagans, even more deserving of death. Speaking on behalf of Christ, Guzmán promised the Cathars slavery and death.

Dominic Guzmán's promises were made good by Crusaders and the Inquisition. Dominic was a friend and companion of the famously brutal Simon de Montfort. We find him by de Montfort's side at the siege of Lavaur in 1211, and at the capture of La Penne d'Ajen in 1212. In the latter part of 1212 he was at Pamiers at the invitation of de Montfort. Before the battle of Muret on 12th September, 1213, Guzmán participated in the council of war that preceded the battle. Like most crusades, the one against the Cathars of the Languedoc was characterised by atrocities and unimaginable barbarity as at Béziers, Bram, Lavaur, and Marmande

In 1214 Dominic Guzmán returned to Toulouse. By this time he had attracted a small group of disciples. He had never forgotten his purpose, formulated eleven years before, of founding a religious order. Dominic had several times been offered, and had refused, the office of bishop. He had bigger plans.

Foulques, the Bishop of Toulouse, made him chaplain of Fanjeaux and in July, 1215, where he established the community whose mission was the propagation of the Roman Catholic faith and the extermination of heretics. In this same year a wealthy citizen of Toulouse put a house at their disposal. In this way the first convent of the Order of Preachers was founded on 25th April 1215. A year later Foulques established them in the church of Saint Romanus.

Dominic had dreamed of a world-wide Order. In November, 1215, a General Council (The Fourth Lateran) was to meet at Rome "to deliberate on the improvement of morals, the extinction of heresy, and the strengthening of the faith". Dominic was present at its deliberations hoping to win permission to establish his new Order. The council was opposed to the institution of any new religious orders, and legislated to that effect. Dominic's petition was refused.

This reversal did not stop Dominic. He simply found a way around what the Catholic Church holds to be an infallible ruling. Returning to Languedoc at the close of the Council in December, 1215, Dominic and his followers adopted the rule of St Augustine, which, because of its generality, could be adapted to any form Dominic might wish to give it. His new order a fait accompli, Dominic applied to the new pope Honorius III in August, 1216. On 22 December, 1216, a Bull of confirmation was issued. He became a favourite of the new pope. The following year he received the office and title of Master of the Sacred Palace, or as it is more commonly called, the Pope's Theologian, In 1217 he formulated a plan to disperse his seventeen followers over all Europe. The following year, to facilitate the spread of the order, Honorius III, addressed a Bull to all archbishops, bishops, abbots, and priors, requesting their favour on behalf of Dominic's new Order. By another Bull later in 1218 Honorius bestowed on the order the church of Saint Sixtus in Rome, which thus became the first monastery of the Order in Rome. Shortly after taking possession of this church, Dominic was given the apparently difficult task of cleaning up the activities of Catholic nuns in Rome. As the Catholic Encyclopedia gnomically puts it " Dominic began the somewhat difficult task of restoring the pristine observance of religious discipline among the various Roman communities of women".

With the support of the pope, Dominic next started a campaign of rapid expansion of his Order, attracting large numbers of followers keen to be associated with a movement sponsored by the papacy. A foundation near the University of Paris was followed by another at the University of Bologna where the church of Santa Maria della Mascarella was placed at the disposal of the Dominicans. In Rome the basilica of Santa Sabina was handed over to them. Next a convent was established at Lyons and then a monastery in Spain. Next came a convent for women at Madrid, similar to the one at Prouille. Then a convent at the University of Palencia, and a house in Barcelona, followed by houses at Limoges, Metz, Reims, Poitiers, and Orléans, then Bergamo, Asti, Verona, Florence, Brescia, and Faenza.. In March 1219 Honorius bestowed upon the Order the church of San Eustorgio in Milan. At the same time a foundation at Viterbo was authorised.

In Lombardy large numbers of people were abandoning the Roman Catholic Church for the Cathar Church, as they had done a few years earlier in the Languedoc. Honorius III addressed letters to the abbeys and priories of San Vittorio, Sillia, Mansu, Floria, Vallombrosa, and Aquila, ordering that members be deputed to begin a preaching crusade under the leadership of Saint Dominic. As it turned out no support was forthcoming, and despite propaganda to the contrary involving a series of wondrous miracles, Dominic's mission failed. As in the Languedoc, those who committed the crime of choosing a religion for themselves would eventually be extirpated by Dominican Inquisitors.

Towards the end of 1220 Dominic returned to Rome. Here he received more concessions for his order. In January, February, and March of 1221 three consecutive Bulls were issued commending the order to all the prelates of the Church.

In 1234 at Bologna he contracted an illness and died three weeks later. In a Bull dated 13 July, 1234, Gregory IX declared him a saint and made his cult obligatory throughout the Church.

Many churchmen had been keen participants in the extirpation of a rival faith, but none exceeded the zeal of Dominic Guzm�n. His faithful Dominicans spawned the Medieval Inquisition, with all its horrors, pioneering new methods of torture and creating new crimes. Ordinances were passed which imposed new penalties for heresy. In 1233 Pope, Gregory IX charged the Dominican Inquisition with the final solution: the absolute extirpation of the Cathars. It was the beginning of the first modern police state in the world.

The role of Dominic himself is debated. When the Catholic Church was less sensitive about the record of the Inquisition, Dominic was hailed as its founder and his role as an Inquisitor was undoubted.

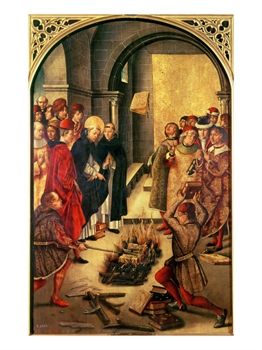

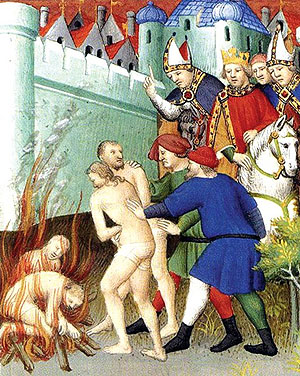

The painting on the left, by Berruguete, previously hung in the Sacristy of the Dominican monastery of Santo Tomás de Ávila (founded by the Dominican Thomas Torquemada, Inquisitor General of Spain). Berruguete painted panels on the life of Dominic Guzman which originally formed part of an altarpiece in the monastery, and this panel may have been one of these. The figures are dressed in the style of the late 15th century and are thought to have been inspired by autos-da-fe that took place in Ávila at this period. Saint Dominic, recognisable by his mantle ornamented with stars, is seated on a throne presiding over the tribunal, surrounded by other judges, one of them bearing the standard of the Inquisition. Below, two of Dominic's victims are tied to stakes awaiting their fate, being burned alive, having been sentenced by Saint Dominic.

As the record of the Inquisition becomes more ever more out of step with modern sensibilities, there has been a tendency on the part of the Catholic Church to dissociate Dominic from his role as father of the Medieval Inquisition - sometimes pointing out that earlier Inquisitions had existed (suggesting that he could not therefore be the founder of "The Inquisition"), sometimes that the Medieval Inquisition was not given formal papal sanction until after his death (suggesting that "The Inquisition" did not exist in his lifetime, so he could not have been any part of it).

A third option for exculpation is employed by the Catholic Encyclopedia under the entry on Saint Dominic "If he was for a certain time identified with the operations of the Inquisition, it was only in the capacity of a theologian passing judgement upon the orthodoxy of the accused. Whatever influence he may have had with the judges of that much maligned institution was always employed on the side of mercy and forbearance, as witness the classic case of Ponce Roger [sic]." This does not square easily on several counts with Dominic's own letter concerning Pons Roger, which shows Dominic acting as a Papal Inquisitor, (commissioned by Arnaud Amaury, on behalf of the Pope). Nor does the letter show him as as being particularly merciful, forbearing or lenient - (see box to the right). To resolve any possible doubt the Dominican master-Inquisitor Bernard Gui (I26I-I33I) in his Life of St. Dominic explicitly claims for Saint Dominic the title of First Inquisitor.

|

Sir Steven Runciman on the Dominicans, referring to the period after the Treaty of Meaux (or Treaty of Paris) in 1227:

Sir Steven Runciman,. The Medieval Manichee, Cambridge University Press, 1999), p 143 |

Dominic is now venerated as St Dominic, and is regarded by many Christians as one of the most holy men ever to have lived. Dominic's legacy has certainly been spectacular. As well as running various Inquisitions, Dominicans monopolised medieval philosophy leading it into the barren desert of scholasticism where it languished until revived by Enlightenment thinkers, not a single significant advance having been made for centuries (except, arguably, by heretical Franciscans).

Modern Dominicans consistently deny that Dominic ever exercised the office of Inquisitor, pointing out that the Papal Inquisition was formally constituted only after Dominic's death. Some see this as perhaps a little disingenouous, since Inquisitors were operating on the authority of papal legates under Innocent III well before the institution of the Inquisition reporting directly to the Pope was given a formal charter. Below is conclusive evidence that Dominic was an authorised Inquisitor even before the start of the Wars against the Cathars in 1209.

|

For Cathars who chose not to deny their faith the penalty was death. So too for those who recanted but then returned to their chosen faith. For confessed first-offender heretics judgements were less harsh - often in the form of penances - but with a more severe reserve judgement if the penances were not fulfilled. This letter was written by Dominic about the year 1208 and concerns a converted Cathar called Pons Roger.

The Latin text can be found in Balme and Lelaidier, Cartulaire, Vol. I, pp. 186-88. There several notable points in this letter: 1. The phrase "By the authority of the Lord Abbot of Citeaux, Legate of the Apostolic See, who enjoined this function on us ..." can only be a reference to Dominic's role as an Inquisitor. No other role fits the circumstances. 2. Most of the penances oblige Pons Roger to live in the same manner as a Cathar Parfait. There are several theories as why Dominic should have required Pons Roger to do this, but they lie outside of the present discussion. Note also the use of the word "command". Genuine penance is by definition voluntary. 3. Sentences of death were rarely committed to writing, but we know that Inquisitors were responsible for burning countless people to death. This sentence has survived possibly because it was passed on someone who was now a Catholic. "Should he refuse to observe these directives, we command that he be deemed a perjurer and a heretic excommunicated from association with the faithful." This is a conditional death sentence. A relapsed and excommunicated heretic would be burned alive. Note also the use of the word "command" again, this time the command is to a third party - something an Inquisitor could do but a simple preacher could not. |

Dominic's canonisation in 1234 was marked by a revealing incident at Toulouse. The bishop, Raimon de Fauga, and a number of Dominican friars had just solemnly celebrated the admission of their new Saint into heaven. As they were leaving the church for a celebratory feast, news arrived that a dying woman in the city had just received the Cathar Consolamentum. The bishop, the Dominican prior and his Dominican retinue promptly set off to deal with this crime. They found the woman at home in bed, gravely ill.

The men of God entered the house where she lay dying. In her delirium she mistook the Catholic bishop for a Cathar bishop and confessed to him her wish to die a good death. At this, and without any sort of trial, the bishop had her removed from the house. Lying on her deathbed, she was carried to a nearby field and there burned alive still in her bed. Their holy mission complete the bishop, prior and friars retired to enjoy their celebratory banquet, having first given thanks "to God and the Blessed Dominic". The Inquisitor Guillaume de Pélhisson recorded the event, pointing out that " God performed these works ... to the glory and praise of His name ... to the exaltation of the Faith and to the discomfiture of the heretics". As both Catholics and non-Catholics have observed at different times, it was a most suitable way to mark Dominic Guzman's canonisation.

|

The quotation is from Guillaume de Pélhisson, Chronicle, translated by Walter L Wakefield, Heresy, Crusade and Inquisition in Southern France 1100-1250, University of California, Berkeley, 1974, pp 215-16. |

Dominc Guzman's own record is recognised in the special language of the Catholic Encyclopedia, which sometimes appears carefully crafted to carry a subtly different message to the devout reader than it does to those familiar with history:

"While his charity was boundless he never permitted it to interfere with the stern sense of duty that guided every action of his life. If he abominated heresy and laboured untiringly for its extirpation it was because he loved truth and loved the souls of those among whom he laboured".

From a secular point of view there was no harm at all in the Cathars, and no reason for them to be even mildly persecuted, let alone burned alive. Yet it is not difficult to find Roman Catholic authorities who seek to justify the Church's genocide and make out that it acted for the best. This is as close as the Catholic Encyclopaedia comes to admitting fault:

Ecclesiastical authority, after persuasion had failed, adopted a course of severe repression, which led at times to regrettable excess.

A Handbook of Heresies, approved by a Roman Catholic Censor and bearing the Imprimatur of the Vicar General at Westminster, refers to Guzmán's "heroic exercise of fraternal charity". His failure as a preacher is not mentioned, nor the fact that even using trickery and torture almost no Parfaits could be induced to abandon their faith. The thousands of Cathar deaths are not referred to except in the most oblique terms:

The long and arduous task was at length successful, and by the end of the fourteenth century Albigensianism, with all other forms of Catharism, was practically extinct.

And the opportunity is taken to condemn Cahar beliefs once again:

This anti-human heresy, by destroying the sanctity of the family, would reduce mankind to a horde of unclean beasts....

|

Dominic's Preaching Friars (Dominicans) and their Inquisition were soon operating throughout Europe, introducing their Inquisitorial techniques to new lands: The following text is from a record of the deeds of the Archbishops of Trier contemporary with the events described.

This extract is from Gesta Treverorum: Continuatio quarto, edited by Georg Waiz, in Monumenta Germaniae historica, Scriptores, XXIV, 400-2. English translation from Wakefield & Evans, Heresies of the High Middle Ages, §45A (PP 267-8). |

There is not a hint of remorse or regret for the holocaust, and one can only assume that, if it could, the Roman Church would act in the same way again if similar circumstances arose in the future, lead perhaps by another charismatic leader like Saint Dominic.

|

|

|

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By St-Dominic

of Guzmán(1475); Pedro Berruguete (around 1450-1504)

commissioned by fellow Dominican

Torquemada, Oil on wood . |

|

|

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By Saint Dominic

Of Guzmán (1475); Pedro Berruguete (around 1450-1504)

commissioned by fellow Dominican

Torquemada, Oil on wood . |

|

|

|

|

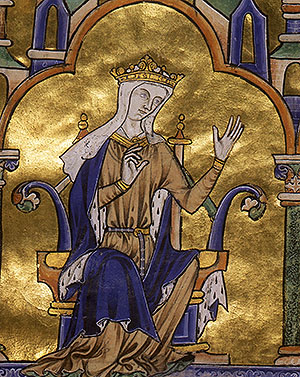

The birth of Dominic Guzman from a Vatican Manuscript, the Legendarium from Hungary, circa 1330. Note the fire breathing dog - a portent. His noble mother wears a crown. He wears ahalo (originally silver ?). From the Early Life of St. Dominic, Legendarium, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vatican City), Vat. lat. 8541, fol. 90v |

|

|

|

|

Saint Dominic and the Albigenses, 1480, Pedro Berruguete (Museo del Prado). |

|

|

|

|

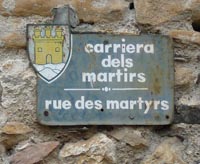

Commemorative Road Sign at Minerve where 140 - 180 Cathars were burned alive for disagreeing with Catholic theology. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By Saint Dominic

Of Guzmán (1475); Pedro Berruguete (around 1450-1504)

commissioned by Torquemada, Oil on wood . 60 5/8 x 36 1/4

(154 x 92 cm). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

St Dominic prays in the traditional manner

with St Francis behind him. From the Early Life of St. Dominic |

|

|

|

|

Saint Dominic (with a halo), Arnaud Amaury, and other Cistercian abbots crush helpless Cathars underfoot - a sanitised version of the persecution of the Cathars |

|

|

|

|

Auto Da Fe Presided Over By Saint Dominic

Of Guzmán (1475); Pedro Berruguete (around 1450-1504)

commissioned by Torquemada, Oil on wood . 60 5/8 x 36 1/4

(154 x 92 cm). |

|

|

|

|

Nicola Pisano, Cathar "heretics" before Saint Dominic the (fictitious) Dispute of Fanjeaux |

|

|

|

|

Saint Dominic was a proponent of the scourge

or "discipline" to mortify the flesh. Here he is

flagellating himself with iron chains. |

|

|

|

![]() In

the 1960s a Belgian Dominican

nun known as The Singing Nun had a hit record with a song

called Dominique, all about Guzmán's life, including

his role in crushing Catharism in the Languedoc - the song has him

converting a heretic, which is perhaps less than a full representation

of historical reality. The song was a number 1 hit in the

UK and the USA. Its jolly tune provides a bizarre counterpoint to

the reality of Guzmán's life, his war mongering, his Dominican

Order and the horrors of the Inquisition.

The Singing Nun committed suicide in 1985.

In

the 1960s a Belgian Dominican

nun known as The Singing Nun had a hit record with a song

called Dominique, all about Guzmán's life, including

his role in crushing Catharism in the Languedoc - the song has him

converting a heretic, which is perhaps less than a full representation

of historical reality. The song was a number 1 hit in the

UK and the USA. Its jolly tune provides a bizarre counterpoint to

the reality of Guzmán's life, his war mongering, his Dominican

Order and the horrors of the Inquisition.

The Singing Nun committed suicide in 1985.

The Words to Dominique by the Singing Nun

|

Dominique, nique, nique s'en

allait tout simplement |

Dominic, nique, nique, just

goes travelling, |

|

A l'e poque ou Jean-sans-Terre de' Angleterre

etait Roi |

At a time when John Lackland was King of

England |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Certain jour, un hérétique

Par des ronces le conduit, |

One day a heretic took him through the thorns |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Ni chameau, ni diligence il parcout l'Europe

a pied |

Without a horse or cart he crossed Europe

on foot |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Enflamma de toute ecole filles et garcons

pleins d'ardeur |

To inflame girls and boys from every school

with ardour |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Chez Dominique et ses freres le pain s'en

vint a manquer |

In Dominic�s house, he and his Brothers ran

out of bread |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Dominique vit en reve les precheurs du monde

entier |

Dominic, in a dream, saw the brother-preachers

in the whole world |

| Refrain | Refrain |

|

Dominique, mon bon Pere, garde-nous simples

et gais |

Dominic, my good Father, keep us simple and

happy |

| Refrain | Refrain |

Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 – 1153),

Saint Bernard (1174)

Bernard had been dead for half a century by the start of the Cathar Crusade - but he was an important figure in the Catholic Church when the Cathar "heresy" in the Languedoc first attracted attention. His influence was felt in many ways during the Crusade.

Bernard was born at Fontaines, near Dijon, in France. His father, a knight, died on crusade. His mother died while Bernard was still a child. His guardians sent him to study at Châtillon-sur-Seine in order to qualify him for high ecclesiastical office and he joined the community at Cîteaux in 1098. The community of reformed Benedictines at Cîteaux grew so rapidly that it was soon able to set up daughter establishments. One of these daughter monasteries, Clairvaux, was founded in 1115, in a valley of a tributary of the river Aube. Bernard, a recent initiate, was appointed abbot. Clairvaux became the chief monastery of one of the five branches into which the order was divided under the direction of the Abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard became the primary builder of the Cistercian monastic order.

In 1128 he was invited to the synod of Troyes, where he was instrumental in obtaining the recognition of the new order of Knights Templar, the rules of which he is said to have drawn up. The Templars were essentially fighting Cistercian monks.

|

Saint Bernard (with the halo) accepting a new recruit into the Cistercian Order, while Cistercian nuns also accept a new recruit

(Vincent de Beauvais, Miroir historial, Musée Condé, MS. 722, f. 210 [detail], Maître François, Paris, c. 1470-80) |

|

His was the main voice of conservatism during the 12th century Renaissance. Bernard was the prosecutor at Peter Abelard's trial for heresy. Bernard had been hostile to Peter Abelard and other scholars at the University of Paris, the center of the new learning based on Aristotle. Abelard was one of the greatest - arguably the greatest - scholastic philosopher of the Middle Ages. Bernard, not an intellectual himself, found it objectionalble that people should learn "merely in order that they might know". For Bernard, education served a single purpose: the indoctrination of priests. The trial was not determined by the strength of the cases put forward by the prosecution and the defence. When Abelard lost he appealed to Rome where Bernard's word was enough to confirm his condemnation. Abelard died soon afterwards.

Towards the middle of the twelfth century the preaching of a priest called Henry of Lausanne was drawing attention to what he saw as flaws in Roman Catholic theology and practices. In June 1145, at the invitation of Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard would travel to the territories of the Count of Toulouse to combat heresy. The threat was not at this time perceived as Catharism, but the teachings of Henry who had come to Occitania having been, as Bernard said, "forced to flee from all parts of France". Here is a translation of an extract from a letter from St Bernard to Alphonse Jordan, Count of Toulouse, written in 1145 before he set off to follow Henry to the Languedoc. It gives an idea of how popular Henry's taching had been.

The Churches are without congregations, congregations are without priests, priests are without proper reverence, and, finally, Christians are without Christ.

(Sancti Bernardi epistolae 241 from Migne, Patrologia latina, CLXXXII, 434-36; Cited by Walter Wakefield & Austin Evans, Heresies of The High Middle Ages (Columbia, 1991) p 93)

Bernards's secretary, Geoffrey of Auxerre, writing in the same year repeats Bernard's comments and goes on:

The life of Christ was barred to the children of Christians so long as the grace of baptism was denied to them. Prayers and offerings for the dead were ridiculed as were the invocation of saints, pilgrimages by the faithful, the building of temples, holidays on holy days, the anointing with the chrism; and in a word, all the institutions of the [Catholic] Church were scorned.

(Sancti Bernardi vita et res gestae libris septem comprehensae; Liber tertius auctore Gaufrido monacho, v 16, 17 in Patrologia latina, CLXXXV, 312-13; Cited by Walter Wakefield & Austin Evans, Heresies of The High Middle Ages (Columbia, 1991) p 93)

With

the invective removed it sounds as though the Reformation has arrived

in the Languedoc some three centuries before Martin Luther introduced

it to Germany. After his visit, Bernard's main impression seems

to have been the shameless corruption in his own Church. The

people of the Languedoc had abandoned the Roman Catholic Church

en mass for unnamed heresies:

With

the invective removed it sounds as though the Reformation has arrived

in the Languedoc some three centuries before Martin Luther introduced

it to Germany. After his visit, Bernard's main impression seems

to have been the shameless corruption in his own Church. The

people of the Languedoc had abandoned the Roman Catholic Church

en mass for unnamed heresies:

... if you question the heretic about his faith, nothing is more Christian; if about his daily converse, nothing more blameless; and what he says he proves by his actions ... As regards his life and conduct, he cheats no one, pushes ahead of no one, does violence to no one. Moreover, his cheeks are pale with fasting; he does not eat the bread of idleness; he labours with his hands and thus makes his living ... Women are leaving their husbands, men are putting aside their wives, and they all flock to those heretics! Clerics and priests, the youthful and the adult among them, are leaving their congregations and churches and are often found in the company of weavers of both sexes.

(from Bernard's sermon 65 on the Caticle of Canticles (or Song of Songs, or Song of Solomon): Sancti Bernardi Sermones super Cantica canticorum, Semon 65 from Sancti Bernardi Opera, Cited by Walter Wakefield & Austin Evans, Heresies of The High Middle Ages (Columbia, 1991) p 130)

Although he does not mention the word Cathar, there are several indications here that Bernard is referring to Cathars: living the Christian ideal; pale through fasting; working for a living; appealing equally to men, women, and Catholic priests. The term "weaver" is frequently used as a synonym for Cathar Parfait, since this was their most favoured itinerant trade. Bernard may have had some sympathy for the Cathars. He never said so explicitly, but he did share some of their views. The world had no meaning for him save as a place of banishment and trial, in which men are but "strangers and pilgrims" (Serm. i., Epiph. n. I; Serm. vii., Lent. n. I). The words could have been taken from a Cathar instruction manual.

Despite any sympathy he might have had, he was happy enough to see those whom he saw as his enemies destroyed. Speaking of heretics, he held that "it would without doubt be better that they should be coerced by the sword than that they should be allowed to draw away many other persons into their error." (Serm. lxvi. on Canticles ii. 15). Killing god's enemies was not merely permitted, but glorious. He asserted in a letter to the Templars "The Christian who slays the unbeliever in the Holy War is sure of his reward, the more sure if he himself is slain. The Christian glories in the death of the pagan, because Christ is thereby glorified". He also pointed out that anyone who kills an unbeliever does not commit homicide but malicide (St Bernard, De Laude Novae Militiae, III (De Militibus Christi). For him all infidels were creatures of Satan. After being asked about how heretics could bear the agony of the fire not only with patience but even with joy, Bernard answered the question in a sermon where he ascribed the steadfastness of heretical "dogs" in facing death to the power of the devil. (Serm. lxvi. on Canticles ii. 15).

Bernard played the leading role in the development of the cult of the Virgin Mary - which many historians have seen as an attempt to counter the prominent role of women in new movements - notably those of the troubadours and the Cathars.

Bernard preached the Second Crusade. His eloquence was extraordinarily successful. At the meeting at Vézelay after Bernard's sermon many of all classes took the cross, most notably King Louis VII of France and his then queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was said that when Bernard preached, women went in fear. Mothers hid their sons from him, wives their husbands, and companions their friends. Bernard proudly informed the Pope of his success in preaching a crusade: "I opened my mouth; I spoke; and at once the crusaders have multiplied to infinity. Villages and towns are now deserted. You will scarcely find one man for every seven women. Everywhere you will see widows whose husbands are still alive". His patter was reminiscent of that of a high-pressure salesman selling to credulous punters:

But to those of you who are merchants, men quick to seek a bargain, let me point out the advantages of this great opportunity. Do not miss them. Take up the sign of the cross and you will find indulgence for all sins that you humbly confess. The cost is small, the reward is great.

Actually the cost was death. Most of those women were soon to become real widows for the crusader army was chopped to pieces in Anatolia before getting anywhere near to the Holy Land. The disastrous outcome of the crusade was a blow to Bernard, who found it difficult to understand why God would let his own army down like this. Perhaps the best solution was that the outcome had been a great success after all, because it had transferred so many Christian warriors from God's earthly army to his heavenly one. Not everyone was convinced. The disaster was so severe that Christians throughout Europe started considering the ultimate blasphemy - that after all God might be on the side of the Moslems.

On receiving the news of the catastrophe, an effort was made to organise another crusade. Bernard attended a meeting at Chartres in 1150 convened for this purpose. He was elected to lead the new crusade, but Pope Eugene III failed to endorse him or his project, and it came to nothing.

Bernard was discredited and looked like a spent force, but his influence was greater than it appeared, and Cistercians in his image would promote further Crusades. The Crusade against the Cathars of the Languedoc was precipitated by the murder of a Cistercian legate, preached by Cistercian orators, initially lead by a Cistercian abbot, supported by Cistercian monks, and even documented by Cistercian chroniclers.

Bernard's comments justifying the killing of God's supposed enemies are echoed in the massacres carried out by a later famous Cistercian abbot and military commander, Arnaud Amaury, the Abbot of Citeaux, most famously at Béziers where he is credited with the immortal command ""Kill Them All, God will know his own"

Bernard was canonised in 1174 and declared a Doctor of the Roman Catholic Church in 1830.

|

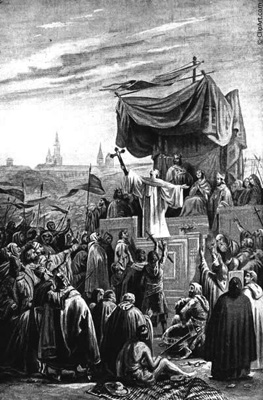

Bernard preaching a Crusade |

|

|

Bernard receiving milk from the breast of

the Virgin Mary at Speyer Cathedral in 1146. |

|

|

Saint Bernard |

|

|

Virgin de la Leche with Christ Child and St. Bernard Clairvaux (detail), By an unknown artist from Peru, 1680. Peyton Wright Gallery, Santa Fe |

|

|

Saint Bernard |

|

|

Cistercian nuns also accept a new recruit by the laying on of hands and touching the head with a testament.

(Vincent de Beauvais, Miroir historial, Musée Condé, MS. 722, f. 210 [detail], Maître François, Paris, c. 1470-80) |

|

|

St. Bernard of Clairvaux |

|

|

The Vision of St Bernard, |

Fulk of Marseille

(Folquet de Marselha, Folquet de Marseille)

also Folc, Foulques, and Folquet

(b. circa 1150 - d. 1231)

Fulk came from a Genoese merchant family in Marseille. He was also a wealthy citizen with some renoun. A contemporary (John of Garlande) later described him as "renowned on account of his spouse, his progeny, and his home." A troubadour, and known as Folquet, he began composing songs in the 1170s and was known to Raymond Geoffrey II of Marseille, Richard the Lionheart, Raymond V of Toulouse, Raymond-Roger of Foix, Alfonso II of Aragon and William VIII of Montpellier.

His love songs were lauded by Dante. There are 14 surviving cansos, one tenson, a lament, an invective, three crusading songs and one religious song (although its authorship is disputed). Like other troubadours, he was credited by biographies of the Troubadours with having conducted love affairs with noblewomen about whom he sang (and with causing William VIII of Montpellier to divorce his wife, Eudocia Comnena).

Folquet's life changed around 1195 when he renounced his former ways and abandoned his family for the Catholic Church. He joined the Cistercian Order and entered the monastery of Thoronet (Var, France). He placed his wife and two sons in monastic institutions as well.

He soon rose in prominence as a Cistercian and was elected abbot of Thoronet. As abbot he helped found the sister house of Géménos to house women, possibly including his abandoned wife.

A few years later Papal legates - fellow Cistercians - deposed the Bishop of Toulouse, Raymond (Ramon) de Rabastens, and were probably instrumental in arranging Folquet's nomination for the position in 1205.

As Bishop of Toulouse, Folquet (now referred to as Fulk, sometimes Fulk of Toulouse (Folquet de Tolosa, Foulques de Toulouse) took an active role in combating Catharism, the favoured religion of the area. Throughout his Episcopal career he sought to encourage Catholic religious enthusiasm and suppress other forms of Christianity (primarily Cathar and Waldensian). In 1206 he created what would later become the convent of Prouille near to Fanjeaux to offer women a religious community that would rival similar existing nearby Cathar institutions.

When a preaching mission led by his fellow Cistercians failed to make any impression other than attracting popular derision, he participated in a preaching mission led by Bishop Diego of Osma. He continued to support this new form of preaching after Bishop Diego's death by supporting Diego's successor Dominic de Guzmán (later Saint Dominic) and his followers, eventually allotting them property and a portion of the tithes of Toulouse to ensure their continued success. (They soon developed into the Dominican Order and Prouille became a Dominican convent).

Because of his abrasive style, Bishop Fulk had tumultuous relations with his diocese, exacerbated by his support of the Cathar Crusade, widely perceived then as now as a war of aggression against Toulouse and the whole region - then independent but annexed to France when the aggression proved successful.

Hated by Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse and by many Toulousains he abandoned Toulouse on 2 April 1211, after the Crusaders laid siege to Lavaur. Soon afterwards he instructed all clerics to leave the city of Toulouse.

He was present at the siege of Lavaur in April-May 1211, which ended in a massacre; he then travelled north to France, where he preached the Albigensian Crusade alongside a fellow Cistercian Guy of les Vaux-de-Cernay. He then returned to the south, participating in the Council of Pamiers in November 1212, in the Council of Lavaur in January 1213, in the meeting with King Peter II of Aragon on 14 January 1213. He was present at the Battle of Muret on 12 September 1213, and at the Council of Montpellier in January 1215. There he was instructed by the Papal legate, Peter of Benevento, to take possession of the Château Narbonnais, the Count's residence, at Toulouse and so returned to the city in February 1215.

In July 1215 Folk issued a diocesan letter instituting Dominic Guzman's brotherhood of preachers which became the Domincan Order. In November 1215 he and Dominic, with Guy de Montfort, attended the Fourth Lateran Council.

Toulousains rebelled in August 1216 against Simon IV de Montfort, their new lord according to the Fourth Lateran Council. Foulques' attempted settlement led to further violence. He tried to relinquish his position but his requests to the pope were declined.

In October 1217, when Simon de Montfort was besieging Toulouse, he sent a group of sympathisers to Paris to plead for the help of the French king, Philippe Augustus. This group included Fulk as well as Simon's wife, the countess Alix de Montmorency. They returned in May 1218, bringing a party of new Crusaders including Amaury de Craon. Fulk spent much of the following decade outside his diocese, assisting the crusading army and the Church's attempts to subdue the region. He was at the Council of Sens in 1223.

After the Peace of Paris ended the Cathar Crusade in 1229, Fulk returned to Toulouse and began to construct further institutions - in addition to the Dominican Inquisition - designed to control the region and extirpate the Cathars. He helped to create the University of Toulouse and also administered an Episcopal Inquisition.

He died in 1231 and was buried, beside the tomb of William VII of Montpellier, at the Cistercian abbey of Grandselves, near Toulouse, where his sons, Ildefonsus and Petrus had been abbots.

|

"Folquet de Marseilla" depicted in his bishop's costume and holding a bible in BnF ms. 854 fol. 61. |

|

|

Saint Etienne's - The Cathedral in Toulouse |

|

|

"Folquet de Marseilla" depicted in his bishop's costume in a 13th-century chansonnier.. BnF MS. 12473 fol. 46 |

|

|

Bishops supervise the burning of "heretics" |

|

Philip II, King of France:

(Philip Augustus, reigned 1180-1223).

Though pressured by Innocent III to take an active role in the Crusade against the Cathars, Philip repeatedly declined, though he did encourage his vassals to join the crusade.

After a twelve years struggle with the Plantagenet dynasty, Philip broke up the great Angevin Empire and defeated a coalition of his rivals (German, Flemish and English) at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. This victory would have a lasting impact on western European politics: the authority of the French king became unchallenged, while the English king was forced by his barons to sign the Magna Carta and faced a rebellion in which Philip and his son (the future Louis VIII) intervened.

Philip was nicknamed "Augustus" by the chronicler Rigord for having extended the royal demesne, the domains ruled directly by the kings of France, as opposed to the territories ruled indirectly by vassals of the king. Philip Augustus transformed France from a small feudal state into the most prosperous and powerful country in Europe.

|

"The burning [Supplice] of the Heretics in 1210" Illustration from the illuminated manuscript Grandes Chroniques de France depicting the burning of Amalrician heretics before King Philip II of France. In the background is the Gibbet of Montfaucon and, anachronistically, the Grosse Tour of the Temple fortress. Jean Fouquet (1455-1460), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris |

|

|

|

|

Battle of Bouvines, 1214 |

|

|

Richard I and his sister Jeanne (or Joanna, or Joan) greeting Philip Augustus, King of France |

|

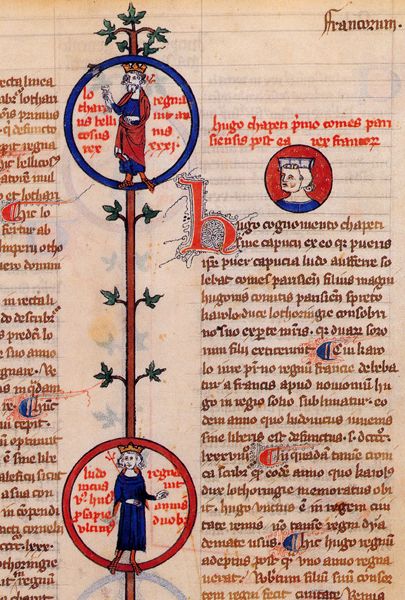

Louis VIII: (reigned 1223-1226).

Louis VIII, the Lion (5 September 1187 – 8 November 1226) reigned from 1223 to 1226. He was also disputed King of England from 1216 to 1217. Louis VIII was born in Paris, the son of Philip II and Isabelle of Hainaut from whom he would inherit the County of Artois.

On 23 May 1200, at the age of 12, Louis was married to Blanche of Castile, following prolonged negotiations between Philippe Augustus and Blanche's uncle John of England.

While Louis VIII ruled as king for only three years, he was an active leader in his years as Crown Prince. In 1215, the English barons rebelled in the First Barons' War against the unpopular King John of England (1199–1216). The barons offered the throne to Prince Louis, who landed unopposed on the Isle of Thanet in eastern Kent, England at the head of an army on 21 May 1216. There was little resistance when the prince entered London and Louis was proclaimed King at St Paul's Cathedral with great pomp and celebration in the presence of all of London. Even though he was not crowned, many nobles, as well as King Alexander II of Scotland, gathered to pay homage. On 14 June 1216, Louis captured Winchester and soon controlled over half of the kingdom. He was proclaimed "King of England" in London on the 2 June 1216. Just as it seemed that England was under his control, King John's death in October 1216 caused many of the rebellious barons to desert Louis in favour of William Marshall, Regent for John's nine-year-old son, Henry III.

Under William Marshall, a call for the English "to defend our land" against the French led to a reversal of fortunes on the battlefield. After Louis' army was beaten at Lincoln on 20 May 1217, and his naval forces (led by Eustace the Monk) were defeated off the coast of Sandwich on 24 August 1217, he was forced to make peace on English terms. The principal provisions of the Treaty of Lambeth were an amnesty for English rebels, Louis to undertake not to attack England again, and 10,000 marks to be given to Louis as a face-saving measure. The effect of the treaty was that Louis agreed he had never been the legitimate King of England.

Before decamping back to France he stole the relics of Saint Edmund the Martyr from the abbey at Bury-Saint-Edmunds, and would later deposit them at Saint Sernin in Toulouse.

From 1209 to 1215 the Albigensian Crusade had been largely successful for the northern forces, but this was followed by a series of local rebellions from 1215 to 1225 that undid many of these earlier gains, especially after the death of Simon de Montfort.

His English adventure over, Louis turned to fighting the Duke of Aquitain (also Henry III, King of England) and the Count of Toulouse. Louis VIII started the conquest of Guyenne, leaving only a small region around Bordeaux to Henry III. Louis was a devout and keen crusader, and distinguished himself by massacres that disturbed even his own war hardened troops, notably when he oversaw the atrocity at Marmande in 1219.

Louis VIII succeeded his father on 14 July 1223; his coronation took place on 6 August of the same year in the cathedral at Reims. As King, he continued to seek revenge on the Angevins, seizing Poitou and Saintonge. In 1225, the council of Bourges excommunicated the Count of Toulouse, Raymond VII, and declared a renewed crusade against the people of the Languedoc. Louis renewed the conflict in order to enforce his royal rights, Amaury de Montfort having sold his feudal rights to Louis. Roger Bernard II (the Great), Count of Foix, tried to keep the peace, but the king rejected his embassy and took up arms against the Counts of Foix and the Count of Toulouse. The took Avignon after a three-month siege, but he did not complete the conquest before his death. While returning to Paris, King Louis VIII became ill with dysentery and died in the Château de Montpensier, on Monday 8 November 1226. The troubadour Guilhem Figueira commented in D'un sirventes far en est son que m'agenssa "Rome, you killed good King Louis because with your false preaching, you lured him away from Paris". His son, Louis IX (1226–70), succeeded him on the French throne.

Louis VIII had thirteen children by Blanche of Castile:

- Unnamed daughter [Blanche?] (1205 - died soon after).

- Philip (9 September 1209 – before July 1218), betrothed in July 1215 to Agnes of Donzy.

- Alphonse (b. and d. Lorrez-le-Bocage, 26 January 1213), twin of John.

- John (b. and d. Lorrez-le-Bocage, 26 January 1213), twin of Alphonse.

- Louis IX (Poissy, 25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270, Tunis), King of France as successor to his father.

- Robert (25 September 1216 – 9 February 1250, killed in battle, Manssurah, Egypt), Count of Artois.

- Philip (20 February 1218 - 1220).[11]

- John (21 July 1219 - 1232), Count of Anjou and Maine; betrothed in March 1227 to Yolande of Brittany.

- Alphonse (Poissy, 11 November 1220 – 21 August 1271, Corneto), Count of Poitou and Auvergne. He married Jeanne of Toulouse, daughter of Raymond VII and Jean of England. his mother, who was regent of France, forced the Treaty of Paris on Raymond VII of Toulouse. It stipulated that a brother of King Louis was to marry Joan of Toulouse, daughter of Raymond VII of Toulouse, and so in 1237 Alphonse married her. Since she was Raymond's only child, they became rulers of Toulouse at Raymond's death in 1249.

- Philip Dagobert (20 February 1222 - 1232[12]).

- Isabelle (March 1224[13] – 23 February 1270).

- Etienne (end 1225[14] - early 1227[15]).

- Charles (posthumously 21 March 1227 – 7 January 1285), Count of Anjou and Maine, by marriage Count of Provence and Folcalquier, and King of Sicily.

|

|

Coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile at Reims in 1223, miniature from the Grandes Chroniques de France, painted in the 1450s (Bibliothèque nationale de France) |

|

Blanche of Castile (1188-1252),

Regent of France (1226-1236)

![]() Blanche

was the third daughter of Alphonso VIII, King of Castile, and

of Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry

II. Under a treaty between Philippe

Augustus and King

John of England, she had married Louis

VIII. When Philip died Louis, their son and the heir to

Kingdom of France (Louis

IX), was twelve years old. Blanche ruled as regent

until he came of age in 1236.

Blanche

was the third daughter of Alphonso VIII, King of Castile, and

of Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry

II. Under a treaty between Philippe

Augustus and King

John of England, she had married Louis

VIII. When Philip died Louis, their son and the heir to

Kingdom of France (Louis

IX), was twelve years old. Blanche ruled as regent

until he came of age in 1236.

The regency of Blanche of Castile (1226-1234) was marked by the victorious struggle of the Crown against her cousine Raymond VII of Toulouse in the Languedoc, against Pierre Mauclerc in Brittany, against Philip Hurepel in the Ile de France, and by indecisive combats against Henry III, King of England. In this period of disturbances the queen was supported by the legate Frangipani, whith whom she was widely roumoured to be engaged in a sexual relationship.

Accredited to Louis VIII by Honorius III as early as 1225, Frangipani won over to the French cause the sympathies of Gregory IX, who was inclined to listen to Henry II, and through his intervention it was decreed that all the chapters of the dioceses should pay to Blanche of Castile tithes for the Albigensian Crusade. It was the legate who received the submission of Raymond VII of Toulouse, at Paris, in front of Notre-Dame. This submission put an end to the Albigensian war and prepared the annexation of the Languedoc to France by the Treaty of Paris (April 1229).

The influence of Blanche of Castile over the government extended far beyond Saint Louis' minority. Even later, in public business and when ambassadors were officially received, she appeared at his side. She died in 1253.

|

Louis IX, Saint Louis, and his mother Blanche de Castille stained glass in the nave of l'église Saint-Louis de Saint-Louis-en-l'Isle in the Dordogne. |

|

|

Blanche of Castile. Detail from Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France in the Bible moralisée de Tolède, dite bible de Saint-Louis, scène de dédicace, circa 1220-1230, The Morgan Library & Museum, Accession number M240 |

|

Louis IX: (1215-1270), St Louis,

King of France (1236-1270)

Louis IX, King of France, was the son of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile, born at Poissy, 25 April, 1215. He ded near Tunis on 25 August, 1270.

The regency of Blanche of Castile (1226-1234) had been marked by the victorious struggle of the Crown against Raymond VII. In the first years of the king's personal government, the Crown fought off an attack led by the Count de la Marche, in league with Raymond's close relative, Henry III, King of England. King Louis IX's victory over this coalition at Taillebourg, 1242, destroyed any hope of success for the uprising planned in Ramon VII's territories to expel the French invaders.

He was eleven years of age when the death of Louis VIII made him king, and nineteen when he married Marguerite of Provence by whom he had eleven children. The regency of Blanche of Castile (1226-1234) was marked by the victorious struggle of the Crown against Raymond VII of Toulouse in the Languedoc, against Pierre Mauclerc in Brittany, against Philip Hurepel in the Ile de France, and against Henry III, King of England. In this period of disturbances the queen was supported by the papal legate Frangipani. Accredited to Louis VIII by Honorius III as early as 1225, Frangipani won over to the French cause the sympathies of Gregory IX, who had been inclined to listen to Henry III. Through his intervention it was decreed that all the chapters of the dioceses should pay tithes to Blanche of Castile to continue the Albigensian Crusade. It was the legate who received the submission of Raymond VII at Paris, in front of Notre-Dame. For the time being, this submission put an end to the Albigensian war and prepared the way for the annexexation of the Languedoc by France under the Treaty of Meaux-Paris in April 1229.

In the first years of the king's personal government, the Crown had to combat a fresh uprisings against French rule, led by the Count de la Marche, in league with Henry III of England. Saint Louis' victory over this coalition at Taillebourg, 1242, was followed by the Peace of Bordeaux which annexed to the French kingdom a part of Saintonge.

As part of the general uprising in 1242 a number of Inquisitors

were massacred at Avignonet by knights from Montségur,

the last remaining Cathar stronghold. This triggered a new military

action to "cut off the head of the dragon". Hughes des

Arcis, the King's representative (seneschal of Carcassonne)

and the Archbishop of Narbonne laid the siege of the Château

of Montségur

( Montsegùr)

in 1243-4, culminating in the burning alive of more than 225 Cathar

Perfects.

Montsegùr)

in 1243-4, culminating in the burning alive of more than 225 Cathar

Perfects.

Louis IX turned his thoughts towards a crusade to the Holy Land. Stricken with a malady in 1244, he resolved to take the cross when news came that Turcomans had defeated the Christians and the Moslems, and invaded Jerusalem. He opened negotiations with Henry III, King of England, which he thought would prevent new conflicts between France and England. By the Treaty of Paris (28 May, 1258) Louis IX concluded an agreement with the King of England. By this treaty Louis IX gave Henry III all the fiefs and domains belonging to the King of France in the Dioceses of Limoges, Cahors, and Périgueux; and in the event of Alphonsus of Poitiers dying without issue, Saintonge and Agenais would escheat to Henry III. For his part, Henry III renounced his claims to Normandy, Anjou, Touraine, Maine, Poitou, and promised to do homage for the Duchy of Guyenne. It was generally considered, that St. Louis made too many territorial concessions to Henry III. Some historians hold that if Louis IX had carried on the war against Henry III, the Hundred Years War might have been averted. St. Louis considered that by making the Duchy of Guyenne a fief of the Crown of France he was gaining a significan legal advantage. The Treaty of Paris, was as displeasing to the English as it was to the French.

By the Treaty of Corbeil, Louis imposed on the King of Aragon the abandonment of his claims to all the fiefs in Languedoc excepting Montpellier, and the surrender of his rights to Provence (11 May, 1258).

|

Saint Louis, King of France, with a Page',

|

|

|

|

|

Louis IX. detail from Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France in the Bible moralisée de Tolède, dite bible de Saint-Louis, scène de dédicace, circa 1220-1230, The Morgan Library & Museum, Accession number M240 |

|

Pope Innocent III (born 1160, Pope 1198 - 1216)

Innocent III, was born Lotario de' Conti, son of Count Trasimund of Segni and nephew of Pope Clement III. Innocent was a keen supporter of Crusades, including the disastrous Fourth Crusade.

|

|